Saint Michael the Archangel in pre-Reformation England, and implications for the ‘butterfly cross’ graffito

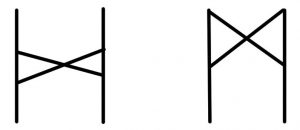

The mark commonly known as the butterfly cross is just one of the many perplexing symbols left on historic stone and woodwork by past generations. In form it tends to resemble a bow-tie shape, simply cut with two upright ends and a saltire cross between them. A proportion of the marks are clearly mason’s or carpenter’s work marks – the symbol being used still as a location mark for timbers, as in the first photograph, showing those in the writer’s own shed, left by a carpenter who didn’t always hit his own laying out marks.

The use of the mark in construction is common, as shown in an example from Tewkesbury Abbey, and the same mark has also been found in the Haute-Vienne region of France.

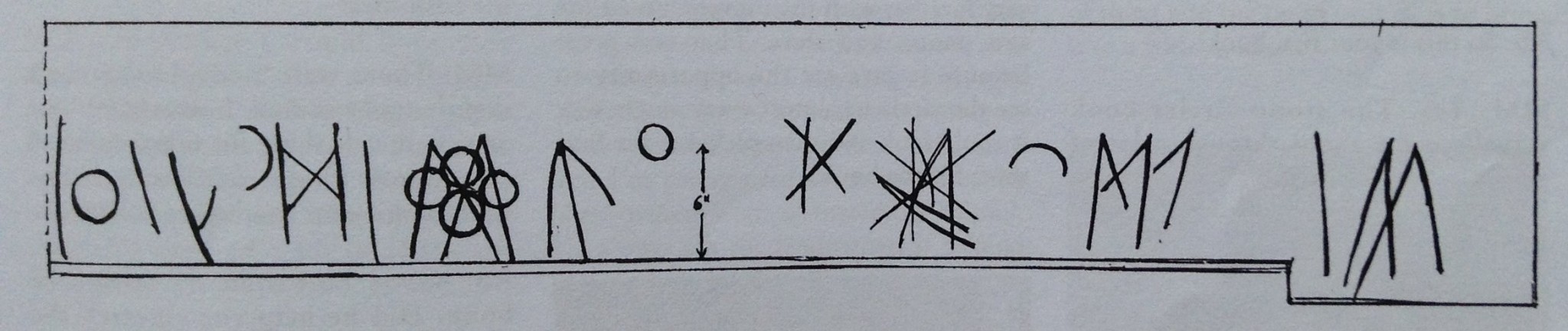

However, aside from the more obvious uses in construction work, the symbol appears to have a symbolic and ritual use of its own. Timothy Easton recorded it in the late 1990s on an early 16th century lintel in Debenham, Suffolk, where it forms part of a long group of symbols inscribed above a large open fireplace. [i]

Numerous other examples have been recorded, and the symbol seems almost ubiquitous – and to occur in places where even the least competent of workmen would hardly have inscribed it; locations in which construction or other practical uses can have no relevance. Examples found around, and, more curiously, inside, fonts have little logic, unless their presence is intended as a safeguard for vulnerable infants, as yet unbaptised – who, if one takes the example to its extreme, are spiritually, and at that moment physically, in a liminal space between heaven and earth.

There is no other obvious explanation for its popularity save that its occurrence in most cases coincides with openings in buildings, or, as recently demonstrated by Linda Wilson, openings in caves. [ii]

Recent work (2015) by Ildar Garipzanov has drawn attention to the extensive use of graphical material, including acrostics and monograms, in Late Antiquity and the Early Christian period, ‘as a mode of visual communication of conceptual information’ [iii], and work published in the same year by researchers from the British Museum revealed symbols of a very similar type to the butterfly cross being used in secure contexts in early Christian Nubia. In this case the symbol has been demonstrated to comprise the Greek form of the name Michael, St Michael, also known as St Michael the Archangel, at that time being considered a powerful protector of the faithful. While it would be foolish to suggest that a Fourth century Coptic symbol has been received, intact, and all its symbology fully comprehended, by the everyday folk of medieval England, it is perhaps possible that the design is one that has travelled, in various poorly remembered forms, across Christendom with the once popular cult of St Michael. The example of the well-known Christian monogram IHS should be borne in mind, forming as it does an abbreviation of the Greek word ΙΗΣΟΥΣ: Jesus.

Michael the Archangel first appears in Abrahamic doctrine in the book of Daniel as ‘one of the chief princes of the Heavenly host’ and as the special guardian or protector of Israel (Dan. 10:13, 12:1). Subsequent early Christian writing associates him with saving true believers from the Devil, battling evil, and being sufficiently powerful to retrieve souls even from hell. In the Judeo-Christian scriptures, only Michael is named ‘The Archangel’, although later Protestant writers added Gabriel, and later still Catholics included Raphael, giving a final group of three, all of whom have subsequently been recognised as Saints, despite not having been mortal. It was Michael, however, who seems to have been regarded as the most powerful protector in the face of evil.

Timothy (Timotheos) the fourth century Archbishop of Alexandria even recommended that the name of Michael be put on the walls of houses: ‘Because the name of Michael will be for them a strong armour. If a man writes these glorious letters upon the (? wall) of his house that is nothing of the enemy will come upon the house nor will the device of wicked men have power over it. But let everyone who shall write if for himself as an amulet take care concerning the compact lest he place it in a place where there is defilement, because great is the power of these marvellous names.’ [iv]

Constantine the Great built a church in his honour at Chalcedon, near Constantinople, in the fourth century AD, and a famous apparition of him reported on Monte Gargano, Italy, around AD 492, led to the spread of his cult to the west [v]. Further visions, generally in high places, including one reputed to have occurred later in the fifth century at St Michael’s Mount, Cornwall, and a further one around AD 708 at Mont St Michel in Normandy, increased his popularity and underlined his role as a heavenly intercessor and powerful protector of humanity. . ‘From the great shrines dedicated to Michael the Archangel at Mont St Michel and Monte Gargano…in the middle ages angels were ubiquitous’. [vi]

The Oxford Dictionary of Saints states that the cult of Michael was popular in Britain from early times, and that by the end of the Middle Ages his church dedications in England may have numbered as many as 686. [vii] During the years of the Reformation and beyond it seems likely that he, with many others was largely lost from view, though the spectacular sites of some of his churches seem to have helped to preserve the memory of his name – John Aubrey, by the time of eighteenth century antiquarian interest, remarking on how many of them stood on high ground or possessed a lofty steeple. Despite probable lost dedications it is estimated that, prior to the Victorian church building boom, six percent of dedications were to Michael [viii] and that in some areas, such as Herefordshire and Devon, he ranked a good deal higher. ‘From the great shrines dedicated to Michael the Archangel at Mont St Michel and Monte Gargano to the elaborate metaphysical speculations of the great thirteenth-century scholastics angels permeated the physical temporal and intellectual landscape of the medieval west…in the middle ages angels were ubiquitous’. [ix]

It is clear that prior to the Tudor Reformation of 1529 onward, which in its latter phases, overseen by Edward VI and Elizabeth I, sought to move the Anglican church to more extreme and ascetic forms of Protestantism, there was a livelier variety of church dedications in England and Wales than we see now. The hard-line Protestants, the Lollards and the Puritans (all of whom existed well before the popular notion of them solely as combatants in the Civil War) were solidly opposed to the Catholic Cult of Saints, which they saw as an idolatrous deviation from a purely Christian devotion to God. The Lollards, in particular, were also violently opposed to the notion of ‘sacred ground’ [x] and the idea of dedicating a church to any named individual.

Henry, and to a greater extent Edward and later Elizabeth oversaw a swift reformation of the established Catholic church, removing images, melting down anything with a precious metal content, whitewashing painted walls and screens, abolishing church feasts and restricting the number of holy days – on which devotions, rather than feasting, were henceforth to take place. [xi]. The Book of Common Prayer, first issued under Edward VI, abolished most of the saints from the calendar. Patronal feasts, celebrating the saint to whom the church had been dedicated, died out. New church dedications were permitted, but became increasingly marginalised and were often not performed. Over the next 180 years of English history the saints were concealed, decried, ignored, and, in many places (unsurprisingly) forgotten.

Consequently, we have a picture of church dedications skewed by time, confusion, and deliberate erasure. Careful work by later researchers has thrown light on a wide range of dedications both to lesser saints, and to those better known, who once had a larger share of the common consciousness, and the medieval popularity of saints such as Michael is now more apparent to us.

The relevance of this to medieval graffiti.

The relevance of this to recorders of medieval draffiti lies in the form of the monogram created from Michael’s name, previously mentioned, which has been reliably recorded at early Coptic Christian sites. [xii] It should be borne in mind that in the early years of Christianity Hebrew, Greek and Latin were all used for learned texts, and that Greek and Roman letters were regularly used as part of Old Roman Cursive script, for writing everyday Latin. The first translation of the Bible was from the Hebrew Septuagint into Greek, in the third century. The Greek letters, even if not the Greek language, would have been familiar forms in the Late Roman – Early Christian world, and for some uses, Greek continued as the language of choice well into the Middle Ages. (Indeed, the name of the Saviour, regarded as supremely sacred, ancient and special, was still being shown in its Greek form in fourteenth-century manuscripts which were otherwise written in Medieval Latin. [xiii]

Add to this the vigorous activity in convening councils, synods and meetings which gripped the Roman Western Empire after the decriminalisation of Christianity in AD 313, and which then continued as the Empire itself receded to the East and Byzantium, and the suggestion of transmission of the monogram along with the cult may be not altogether far-fetched.

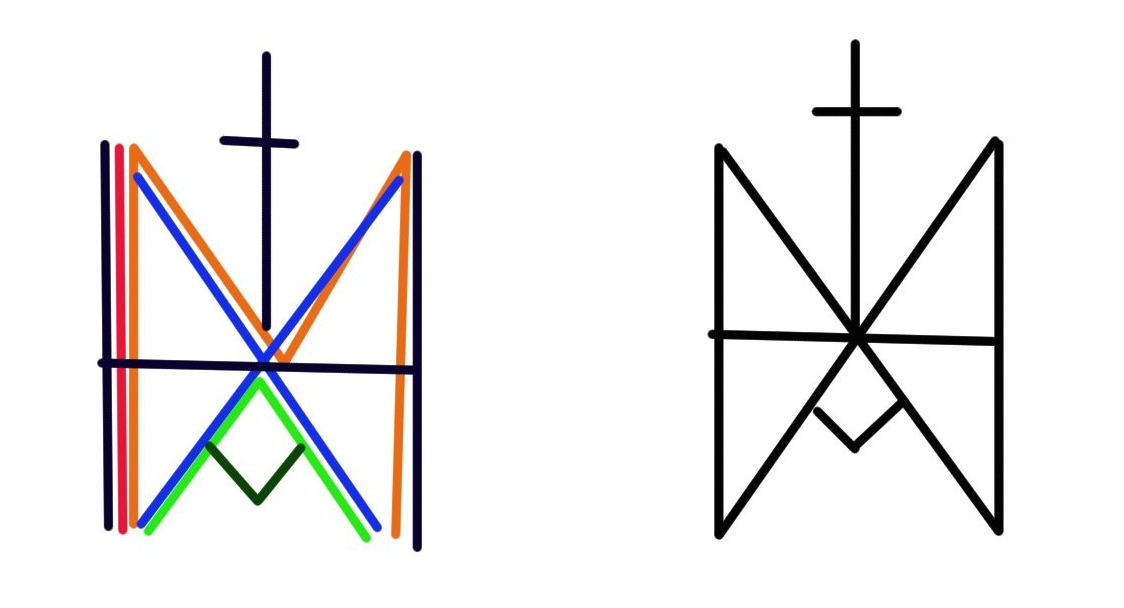

In Greek capitals the name Michael is expressed as ΜΙΧΑΗΛ. Superimposing all the letters to form a monogram using the smallest number of strokes produces a figure akin to a bowtie with a line across it.

The symbol has been found both on walls in Nubia, in early Christian settlements, and – surely a place where no mason would carve a mark – as a tattoo on the thigh of a Coptic Christian woman. [xiv]

The question remains whether a notion of the protective uses of the monogram of Michael the Archangel could have travelled across the early Christian world along with his cult popularity, and whether a debased version, missing the horizontal strokes of the H and the A, could be the root of the ‘butterfly cross’ that we now recognise as an apotropaic symbol.

New evidence from St Andrew’s Church, Harberton, Devon and previously recorded symbols from Norwich Castle, both seem to suggest a debased form of the Greek original, the literal meaning of which was no doubt forgotten very soon after its invention: Greek may have been a common script in the early Church, but literacy in general was probably a good deal less common among its foot soldiers, and certainly by the medieval period would have meant very little to English church-goers.

The Harberton graffito has been plastered over and then later scoured clean, possibly by the Victorian restorers, leaving the crossbar partially filled in.

The reasoning behind the use of the saltire or butterfly cross has not yet been made specifically clear by any written source, however, Timothy Easton was told by one Suffolk blacksmith that the x with two adjacent uprights (forming the ‘butterfly’ cross) was put on window and door hinges and latches because the uprights represented the opening and the cross barred the way to anything evil. [xv]

Curiously, another reading of the symbol, as a form of the Saxon D rune, for Daylight, (left, below) works equally well with the M rune for Michael (right, below). [xvi]

Given the elapse of time and the effects of the Reformation in Britain, it is difficult to justify a continued knowledge, however shaky and debased, of the uses of the monogram of St Michael the Archangel. However, it is very tempting to see a parallel between the injunction of Archbishop Timothy and the information given to Timothy Easton, together with the uneasy sensation of a folk memory of the symbol surviving well beyond its original religious exposition. This possibility is hard to ignore.

Author: Rebecca Ireland

July 2018

Footnotes:

[i] Easton, Timothy. Ritual Marks on Historic Timber in Third Stone, 38, pp 3-17, Third Stone, Devizes, 2000

[ii] Wilson, Linda. By Midnight, By Moonlight: Ritual Protection marks in caves beneath the Mendip Hills, Somerset in Hidden Charms,Transactions of the Hidden Charms Conference 2016, pp41-51, Northern Earth Books, 2017

[iii] Garipzanov, Idlar. The Rise of Graphicacy in Late Antiquity and The Early Middle Ages Viator, vol. 46, No. 2 pp.1-22, Brepols, Turnhout, Belgium 2015

[iv] Vandenbusch, M and Antoine, D. Journal of the Canadian Centre for Epigraphic Documents v 1, Under St Michael’s Protection: a Tattoo from Christian Nubia, p18, University of Toronto, 2015

[v] Farmer, David. Oxford Dictionary of Saints, p368 (a) OUP Oxford, 1978

[vi] Keck, David. Angels and Angelology in the Middle Ages, p3. OUP New York, Oxford, 1998

[vii] Farmer, David. Oxford Dictionary of Saints, p368 (b) OUP Oxford, 1978

[viii] Morris, Richard. Churches in the Landscape, p53, M. Dent (Phoenix), 1989

[ix] Keck, David. Angels and Angelology in the Middle Ages. p3, OUP New York, Oxford, 1998

[x] Thomas, Keith. Religion and the Decline of Magic, p65, Peregrine (Penguin), 1978

[xi] Hutton, Ronald. The Rise and Fall of Merry England, p73-74, OUP Oxford, 1994

[xii] Anderson, Julie. Soba II: Renewed excavations within the metropolis of the Kingdom of Alwa in Central Sudan. ‘Christian graffiti from the excavations at Soba East, 1989-1992,’ pp 185-209, The British Museum and the British Institute in Eastern Africa. London, 1998

[xiii] Kieckhefer, Richard. Magic in the Middle Ages p 69, Fig. 6: Christ Blessing the Herbs. CUP, 1989

[xiv] Vandenbusch, M and Antoine, D. Journal of the Canadian Centre for Epigraphic Documents v 1, Under St Michael’s Protection: a Tattoo from Christian Nubia, p18, University of Toronto, 2015

[xv] Easton, Timothy, in Hutton, R (ed.) Physical Evidence for Ritual Acts, Sorcery and Witchcraft in Christian Britain. Apotropaic symbols and other measures, p55, Palgrave Macmillan, 2016

[xvi] Cramp, Rosemary. Grammar of Anglo-Saxon Ornament, Chapter 6, p xlix, Epigraphy, fig 28. Runes: system of Transliteration.