The Discoverie of Witchcraft, wherein the Lewde dealing of Witches and Witchmongers is notablie detected, in sixteen books … whereunto is added a Treatise upon the Nature and Substance of Spirits and Devils. Reginald Scot. William Brome, London, 1584.

‘How diverse great clarkes and good authors have been abused in this matter of spirits through false reports, and by means of their credulitie have published lies…’

In the late 1500s, 15 years before King James VI&I indicated royal approval for the sport of witch hunting, Reginald Scot, disturbed both by the still enthusiastic acceptance of the powers of witches by the majority of the population, and by the extraordinary violence of some of the steps taken against them, published a lengthy and insistent polemic against such a mistaken belief .

The son of a minor country gentleman, Reginald (or Raynald as he signed himself) was born about 1538. At around the age of 17 he went to Oxford, but left the university without a degree. His writings ‘attest some knowledge of law’ (Dictionary of National Biography (DNB)’) but he is not known to have joined any inn of court. He spent most of his life as an active country gentleman, managing his own inherited property and acting as business manager for a wealthier cousin. It is clear from his writing that, whatever his achievements as an undergraduate, he was literate and well read. He had a knowledge of Greek and Latin – sufficient to argue the definitions of the Biblical words which, by his time, had been reduced, through mistranslation or wilful misunderstanding, to the single, pejorative, ‘witch’.

According to his DNB entry, which provides a useful antidote to other more excitable accounts, ‘Scot’s enlightened work attracted widespread attention’ and made great impressions on the magistracy and clergy. A more enlightened point of view on alleged witches was clearly possible, and acceptable to many, in his time. Unfortunately superstition was not so easily overcome, and many writers came to its rescue, most notably, perhaps, James VI of Scotland. He defended his belief in witches in his ‘Dæmonologie’ (1597), where he described Scot’s work as ‘damnable’, and finally, on his accession to the English throne, he ordered all copies of Scot’s ‘Discoverie’ to be burnt. The fact that there were copies surviving to provide reprints in 1651, in London, indicates the success of this attempt to suppress it. Copies were also available from abroad, where it had met with a favourable reception.

In 1886, Dr Brinsley Nicholson edited a handsome limited edition reprint of the first edition of 1584, with the additions from a revised version of 1665, which is now available free, online. In 1930 Montague Summers wrote the introduction to a further reprint of the 1584 text, expressing his own solidarity with James VI & I.

What, then, did Raynald Scot write in his sixteen books? The first thing is to say that although he splits his work into sixteen books, each divided into chapters, the sum total is a little over 280 moderate-sized paperback pages. It’s really not an early modern blockbuster in size, and the less voracious reader can feel confident of getting to the end. Neither of the readily available imprints is a facsimile, so although the spelling is early modern, the typeface isn’t. The 1886 font is considerably easier on the eye than the one used in 1930, which appears to have been deliberately chosen to make the volume look old.

The first eleven books cover Scot’s reasoning as to what events and powers are erroneously attributed to witches, how foolish and gullible people are to think that witches have any power, and exposing various tricks and stage magicians’ props by which the gullible are, of course, easily fooled. He also comments on the methods approved at the time for questioning supposed witches; encouraging everyone to read the details and then proposing that anyone, subjected to that treatment, might say anything.

It is an entirely sane and reasonable series of chapters, which might come as a surprise to anyone who has read the reports of witch trials of the time and assumed that they represented the only view of events.

At the start of Book 6, Scot discourses, finally, on the words at the core of the biblical justification for all witch persecution in Christendom: ‘thou shalt not suffer a witch to live’. We’ve all heard it. Those of us with an interest in the subject have known for a while that it’s a very subjective translation. It involves a journey from Hebrew, via Greek, to Latin and eventually, in the UK, into English. The Hebrew original indicates an already lost and forgotten form of female practitioner and her fate is not specifically death: it could, as pointed out by Ronald Hutton (The Witch, 2017, p52) mean banishment from living in her community. The original Hebrew is archaic and open to translation. The next translation, the Greek Septuagint, rendered the word for the practitioner as pharmakia or herbalist, which sounds innocuous, though in other contexts it might translate as poisoner. It appears that up to this point everyone knew very well that there were good potion makers and bad potion makers, and, more to the point, that they knew the difference. The 4th century Vulgate Latin word used for the undefinable Hebrew practitioner, on which later translations depended, was maleficos, which could be taken to mean poisoner, but could also be read as sorcerer/sorceress, which of course could be reduced neatly to ‘witch’. Ignoring the subtleties and uncertainties of the original source, and with Scot, and others of the same mind, pointing out the questionable accuracy of the accepted translation, the official version kept it.

The remaining five books are largely given over to describing and debunking various charms, spells and recipes supposed to be magical. The problem for Scot’s work, whether he knew it in his time or not, is that these sections have subsequently been hijacked as a Grimoire by people actively seeking spells – a side effect he can hardly have contemplated.

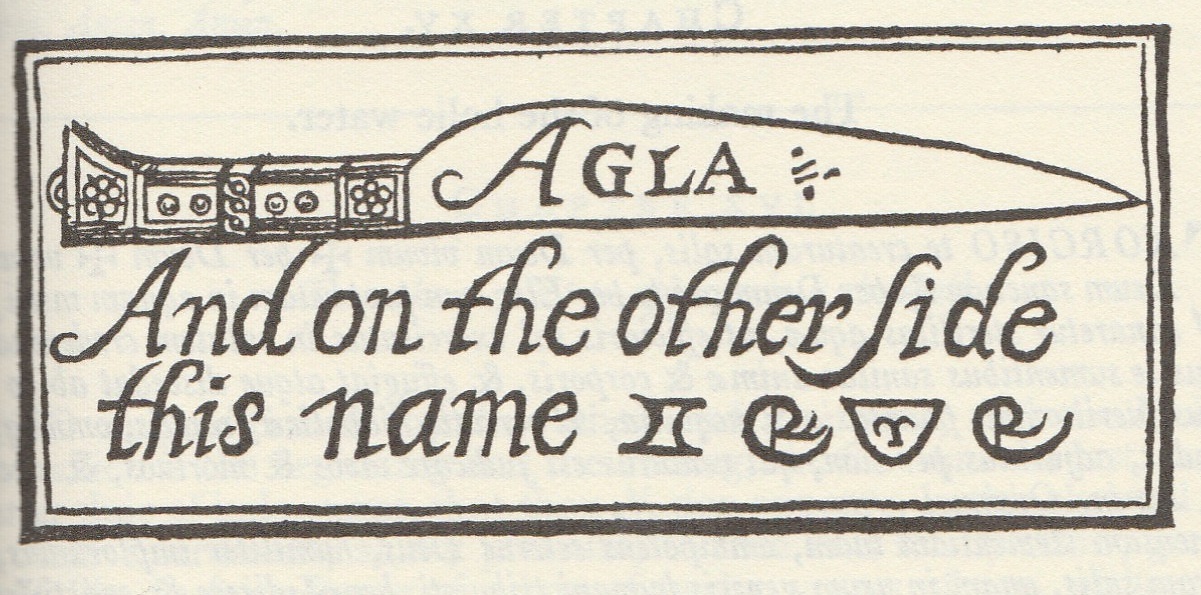

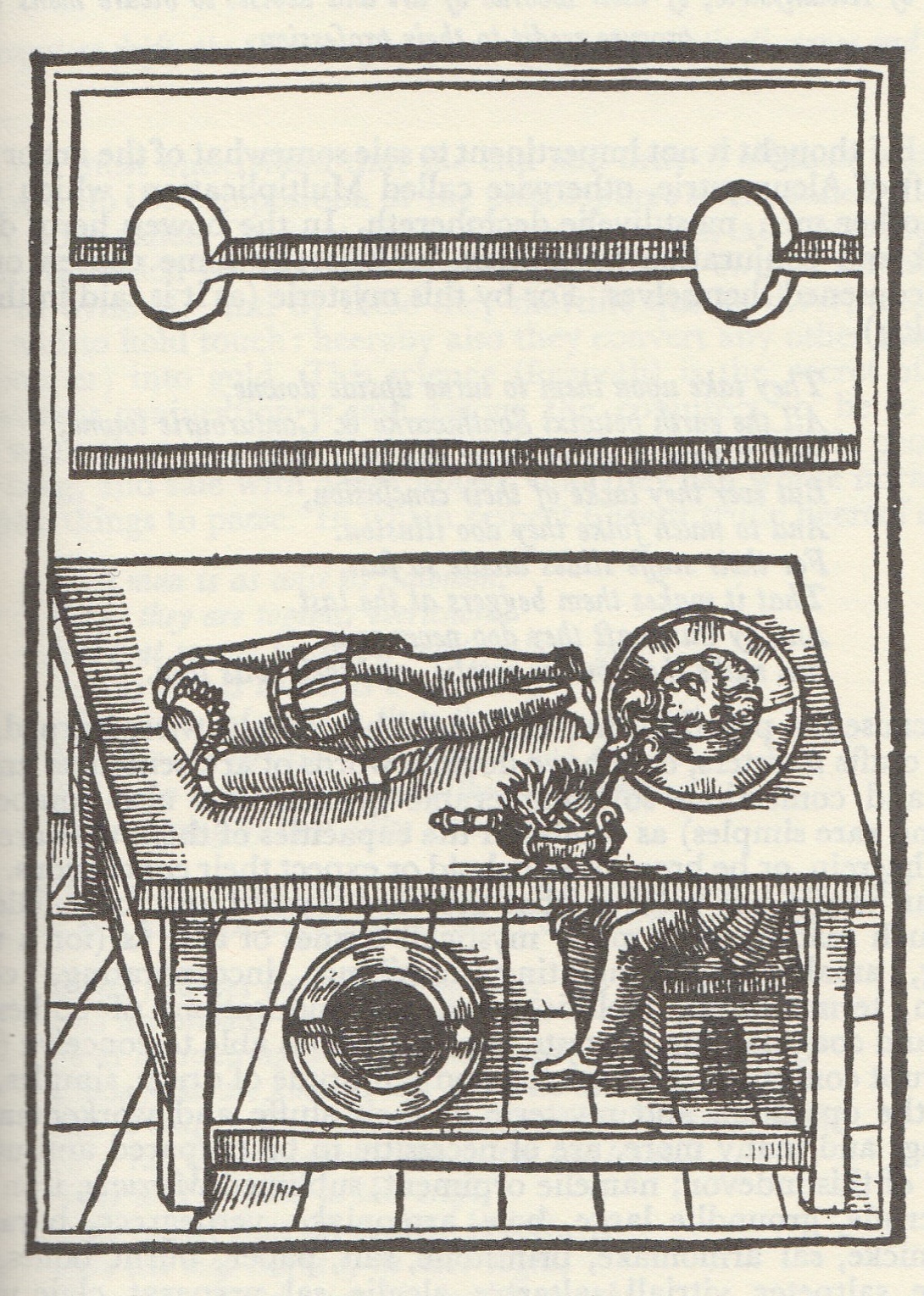

In terms of information helpful to the graffiti hunter, Raynald Scot’s illustrations add little. There is an example of a prepared knife for conjuring, with the letters AGLA on it (book 15, ch. 14), and a few largely alchemical diagrams. There is also a neat illustration of how the stage magician would construct a platform in order to be able to present a liv e, but severed, head in a basket ( book 13, ch.34).

e, but severed, head in a basket ( book 13, ch.34).

One of the prayers-cum-charms is however interesting in that it gives an indication of the continuing cult of St Margaret of Antioch – a saint declared apocryphal as early as 494, but in fact surviving in the popular imagination well into the medieval period and beyond.

Saint Margaret of Antioch was a virgin saint who, having been cruelly tortured for her faith, burst out of the belly of a dragon which had subsequently tried to eat her (the devil) and thereby triumphed. She vanquished demons, often being portrayed with a dead dragon, or her foot on a dragon (the devil again) or thrashing a demon, sometimes with a hammer. Her areas of special interest included: childbirth, pregnant women, dying people, kidney disease, peasants, exiles, virgins and the falsely accused. And her badge was the marguerite, or daisy. You can see where this is leading.

Scot records a lesson for St Margaret’s day, from the Catholic rite (which as a good Protestant he naturally deplores as superstitious) which includes the phrase: ‘…grant therefore O father, that whosoever writeth or readeth or heareth my passion, or maketh memorial of me, may deserve pardon for all his sinnes’… It is at this point surely worth considering whether every single daisy-wheel diagram recorded is categorically dedicated to an unspecified apotropaic role, or whether some may in fact have been dedicated as memorials to St Margaret of Antioch, for the forgiveness of sins, or for the protection of the petitioner for other reasons. Daisy wheels are very old; they have undoubtedly changed their local meanings across time and space. It may well be that this is a further translation that may be attributed to them.

Scot continues his own cautionary tale in a more typical fashion; citing the case of a young man determined to defeat the devil who mistakenly beat an innocent woman to death, thinking she was the devil in disguise.

Raynald Scot was an enlightened and humane writer, and even in the original 16th century spelling his work is lucid – if inclined to get repetitive as he tries to drive home his very simple message with more and more examples. This is a book well worth reading, for an insight into the level of intelligent scepticism that existed in the era that immediately preceded the horror of the Jacobean witch trials, as well as into the practices of a wide section of society who would shortly be either supporting, or suffering from, that horror.

Review by Rebecca Ireland.

Note: The Discovery of Witches by Witch-Finder General Matthew Hopkins is also available, but a very different read.

For anyone requiring the text in a clear font, with a straightforward biographical introduction, I would recommend:

The Project Gutenberg EBook of The Discoverie of Witchcraft, by Reginald Scot, edited by Brinsley Nicholson. London. 1886.

Release Date: November 22, 2019 [EBook #60766]

A hardback reprint of the 1886 edition is also available: Wentworth Press (7 Mar. 2019)

Amazon, £26.95

ISBN-10: 0530555611

ISBN-13: 978-0530555614

Paperback edition: Dover Publications Inc. New edition, 1 May 1990, an unabridged republication of the John Rodker (1930) edition, with introduction by Montague Summers. The introduction may be unpalatable to anyone who feels that a firm personal belief in ‘…a horrid foundation of fact of evil and of sorcery’ is an insufficient defence of the witch persecutions.

Available from Amazon for £10.99

ISBN-10: 0486260305

ISBN-13: 978-0486260303