Bath Abbey, Bath and Northeast Somerset

The Abbey Church of St Peter and St Paul, better known as Bath Abbey, has been undergoing a £19.3 million programme of major works, funded largely by the Heritage Lottery Fund, in order to repair the Abbey’s collapsing floor, install a new heating system using the nearby hot springs and to provide a comfortable and accessible space for all its users and visitors. Archaeological investigations, including graffiti recording, have been carried out by Wessex Archaeology as part of the development, and alongside their work Wiltshire Medieval Graffiti Survey have been recording the graffiti uncovered by the various rearrangements of the internal fittings, and also those in less publicly accessible areas.

The Anglo Saxon Chronicle states that land was given, c 675 AD, by Osric to an abbess to found a nunnery at Bath, and references to a Christian community there occur in 758, the 770s and 796. The early Christian community formed its buildings around the remaining Roman structures, and the first Abbey of St. Peter probably lay to the immediate east of the Roman temple and baths complex, under the west end of the current building. The long term human use of the site has been highlighted by finds dating to the Mesolithic period, recovered during the current archaeological investigations.

The abbey was built principally of Bath Stone (limestone), largely during 1499-1533 but with substantial Victorian restorations. The present abbey building is now completely free-standing, but in the medieval period was surrounded by monastic buildings. After the Reformation various houses and shops attached themselves to the church until the last were cleared away during the restoration of 1833, however the occupants of the houses, both attached and simply nearby, were in the habit of using the Abbey as a thoroughfare and at least part of the considerable variety of graffiti to be found is likely to be a result of that. In the main body of the church, inscriptions can be found on all the aisle columns, and on the older tombs, the walls of the Abbey being almost completely covered in monuments and memorial plaques.

Along the north aisle the majority of pillars have been tagged with initials of all dates, not all of them accessible to photograph in 2019, though with the planned re-ordering of the interior this may well change.

Throughout the Abbey the floors as well as the walls are thick with memorial slabs, and the honeycombing effect of vast numbers of burials under the floor has contributed to its recent instability.

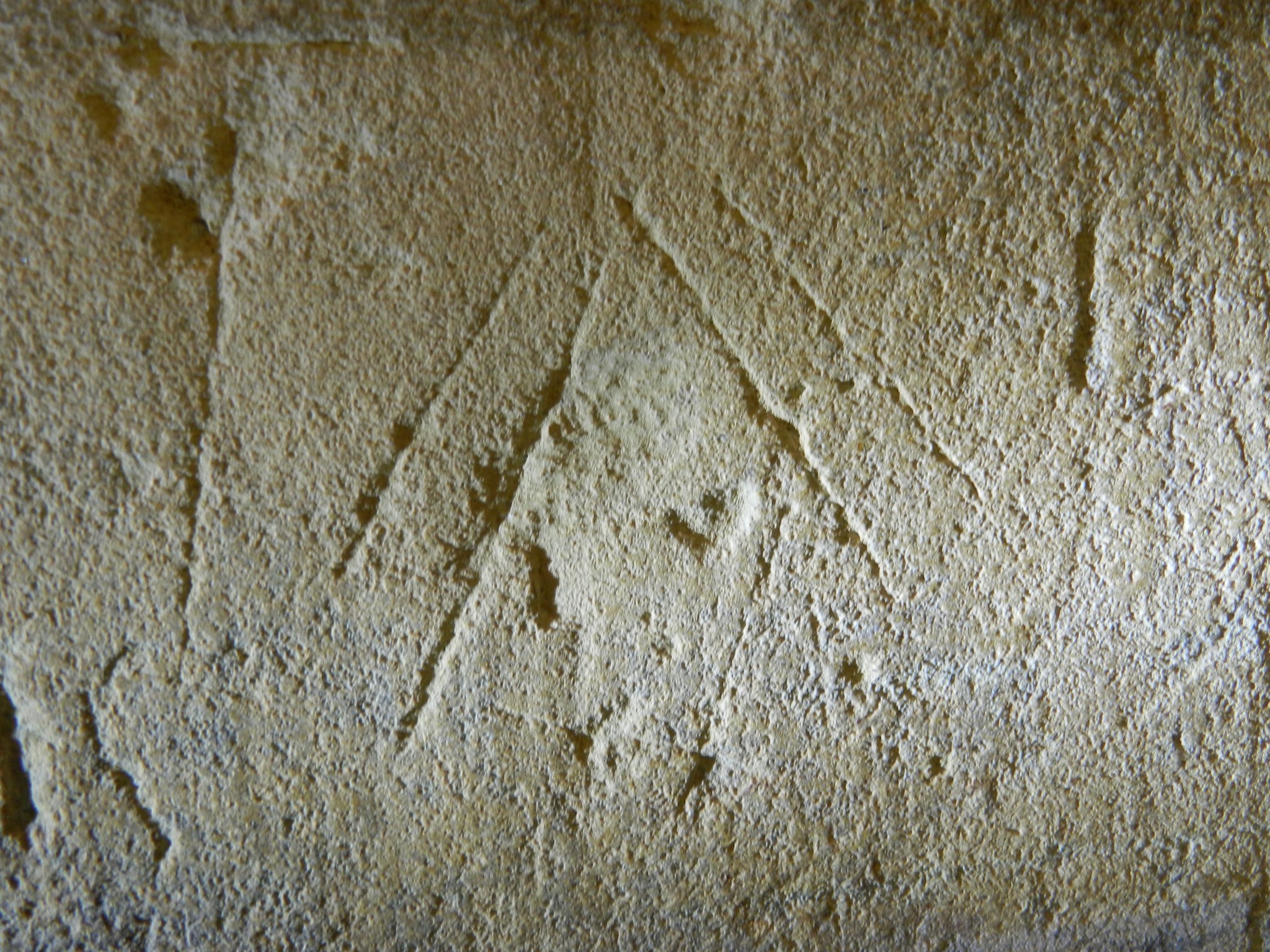

Along the South Aisle a similar collection of graffiti to that on the north can be observed on the pillars, with (at the time of visiting) slightly more apotropaic symbols being visible.

Fortunately for any budding graffiti enthusiast, the Wiltshire Graffiti Survey have been running behind the scenes tours to give a taste of the volume and variety of graffiti they have been discovering, and a brief tour of the north east tower stairs with Director Tony Hack showed just a fraction of what is there, and gave a sense of the vast scale of what, in smaller churches, would be a straightforward recording exercise.

Marian marks, merchant marks, incised circles, daisy wheel marks and gouged hole patterns all occur, as might be expected, but the overwhelming content in this stair well came from the sheer volume of individuals, over a period of hundreds of years, who had passed up and down and written their, or others, names or initials and dates. A self important workman, writing his name and, apparently, chiselling out those of his rivals, came into view about half way up. Stair 100, the number carefully incised in the wall beside the step and then almost as carefully amended to 109, presumably as a joke – it is stair 100: bell ringers and other Abbey habitues are still irked by it. A huge screed of elegantly pencilled script flowed up and across the outer curve of wall, defying the the confined space. An inscription dated to the end of the first world war ‘God bless them all’, and a poignant list of dates from the second.

Finally, at the very top, at the top of the corbel on the top of the newel post, my companion, a ringer from the abbey, spotted ‘T Hogsflesh’ a name known from two peal boards in another Bath church and here memorialising himself by tagging the Abbey.

On a separate visit to the Abbey, a rare swastika was found, along with a couple of examples of daisy wheels and interlinked compass circles. There are also examples of Marian marks and a cross with a decorated stem that may be a merchant’s mark.

Bath Abbey is, even under normal circumstances, an exceptional place to visit. During the current works, despite the upheaval, it is completely fascinating and well worth an extra visit.

Report by: Rebecca Ireland and Anthea Hawdon

Bath Abbey website here.

Bath Abbey Office

11A York Street

Bath

BA1 1NG

Telephone 01225 422462 Monday to Friday 9.00am – 4.00pm (Answerphone available outside these hours)

Email: office@bathabbey.org

The office is generally open to visitors Monday to Friday 9.00am – 1.30pm

Search terms: Marian marks, merchant marks, daisy wheel, incised circle, part circle, diagonal lines, dot pattern, gouges, butterfly cross, scissors, Antony, Bingham, Cobhed, Down, Harvey, Hogsflesh,first world war, second world war, 1914-1918, AD, AS, CB, CT, DD, DT, EA, ED, EG, F, GT, GS, H, HM, I, IG, IHL, IW, JA, NP, P, PFP, PW, RR, RWA, TH, WF, WT 1604, 1606, 1730, 1740, 1752, 1777, 1944, 1945, 1948