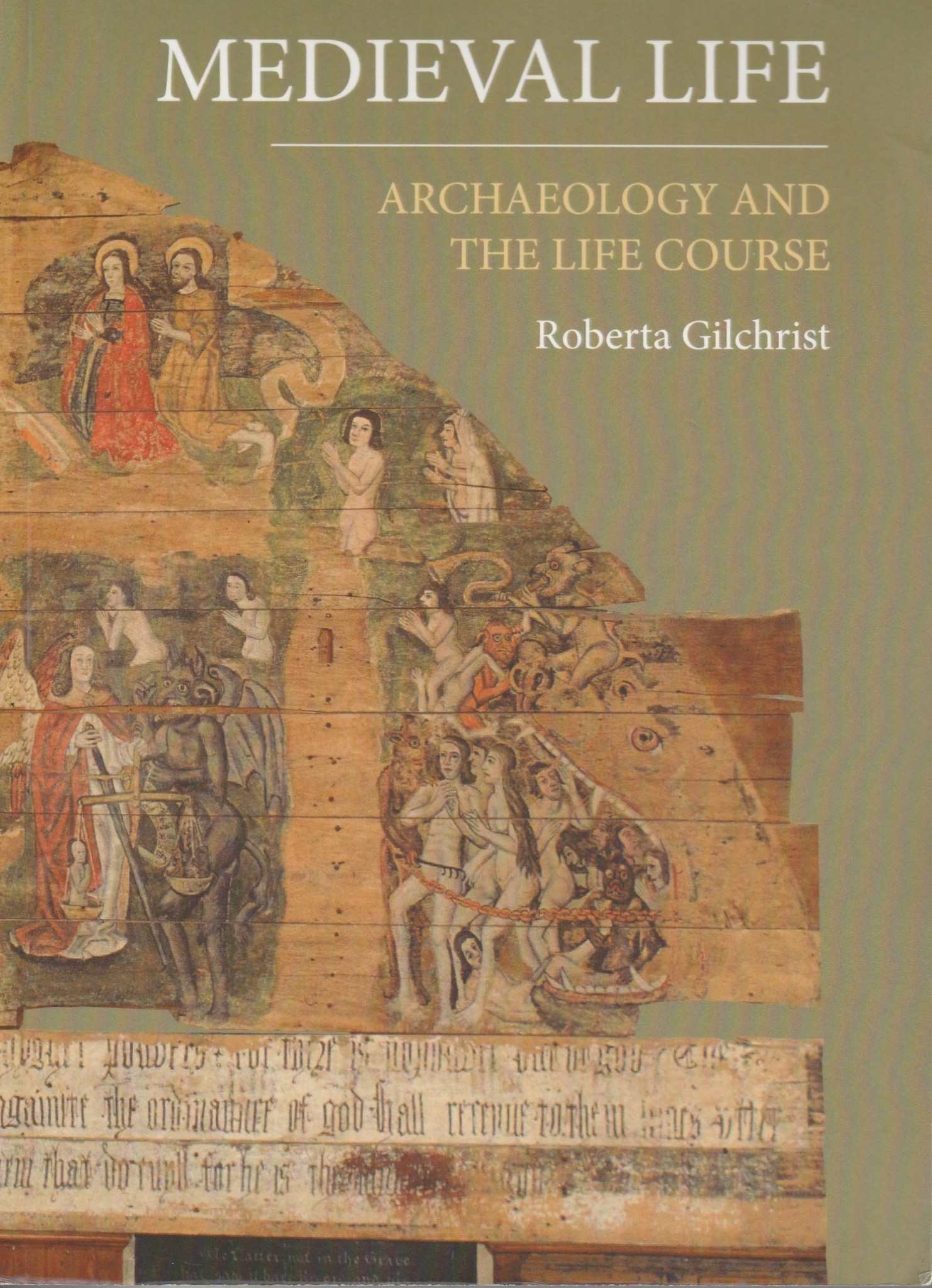

Medieval Life: Archaeology and the Life Course. Roberta Gilchrist, Boydell Press, Woodbridge 2012; paperback 2018.

The aim of this book, as stated on its rear cover, is to explore how medieval life was actually lived, from birth to death and covering every aspect of the life course in between. It is, as Professor Gilchrist notes in her preface, the first detailed study to adopt and develop the framework of life course theory – formerly the province of social scientists – for use in archaeology. For the student of folk belief, unofficial ritual and historic graffiti it is probably the most useful introduction to the medieval period yet published.

Previous studies of this period (given for the purposes of this study as 1050-1450 CE/AD) have tended to focus either on separate episodes in, or stages of, life (frequently pursuing a single stage of life or a single occupation for an entire publication). Roberta Gilchrist has integrated the whole sequence of likely major episodes throughout a lifespan, indicating their relevance to the individual at different stages in their own life and in relation to those around them, stressing ‘the inter-linkages between phases of life’.

In support of this longitudinal study, Professor Gilchrist utilises data from many of the well-known archaeological sites of the period across England, and from a large number of museum collections. She weaves these together to form a tapestry of medieval life, as it may have been lived, that is far more complex and intriguing than many previous texts might have led one to believe.

Of especial interest to the hunters of folk practices and historic graffiti is a reference to Daisies, probably once connected etymologically with St Margaret the Virgin of Antioch (i.e. Marguerite, aka Daisy) Virgin-Martyr and Vanquisher of Demons. St Margaret of Antioch was declared apocryphal by Pope Gelasius I in 494. The marguerite, however, seems to have gone on to have a quite separate and much wider afterlife. By the period covered by Roberta Gilchrist the daisy, along with the pearl, had become symbolic of all virgin maids; the marguerite was taken as a reference to the Virgin Mary, and the word Margareta had come to refer ‘to both the pearl and to the maiden’.

A reference to fish, as a Christian symbol, occurs later in the book, indicating that, rather than dying out in antiquity and being revived in the 20th century, the symbol had a currency at least as far as the medieval period. There is, of course, debate as to whether the symbol refers to Christ the fisher of men, or harks back to an early Christian acronym using the Greek word for fish, icthys – ΙΧΘΥΣ – which can be quickly and simply indicated as a pair of interlinked arcs.* The upshot is, however, that the finds of the fish symbol exist in medieval contexts and indicate its afterlife as a Christian emblem.

Further specific references to magic and charms are, inevitably, dotted through the pages of this book: medieval life was full of dangers, seen and unseen, and it would have been foolhardy to try to deal with it unaided. Some items are clearly Christian in intent, if not in ultimate origin, others are less certainly so. Chapter 5, in dealing with church and cemetery, and eventually with death and burial, lists a high concentration of finds with potential apotropaic function: grave goods. A later section, in chapter 6, deals with ‘special deposits’ in medieval buildings – this is the section for dried cat enthusiasts – and with the creation of protective graffiti, acknowledging the opening up of this field of investigation by Ralph Merrifield and Timothy Easton, and the ‘stubborn reluctance’ of mainstream archaeology to address the phenomenon.

This is a skilful study, wide ranging and deeply researched, as one would expect from a senior academic at a well-respected university. It is handsomely illustrated, with many of the technical archaeological drawings from original excavation reports. There are no less than 14 Appendices: enough spreadsheets on artefacts and contexts to satisfy the most data struck. What makes it an exceptional pleasure is its steady readability. It is not a quick fix: there is a great deal to absorb and digest, but it is a very satisfying read. It is full of detailed and unexpected information – information that, though already published, has not previously been placed in the context of the wider medieval world, and has not been so readily accessible to a more general readership. I recommend it unequivocally to anyone interested in any aspect of the English Medieval period.

*[The expanded acronym, dangerous to fatal at times, is, in translation: Jesus Christ God Son Saviour. This, reduced back to ΙΧΘΥΣ (ichthys/fish), can also be compiled – literally, one letter on top of another – to form a wheel, and is found in this form on early Christian sarcophagi. The word itself was symbolic of a whole phrase, but could in turn be ultimately reduced to a single symbol. Apart from an obvious need for secrecy in times of persecution, the late classical period loved a word game].

Review by Rebecca Ireland

Medieval Life: Archaeology and the Life Course. Roberta Gilchrist, Boydell Press, Woodbridge 2012, paperback 2018.

ISBN 9781843837220 (hbk)

ISBN 9781783273065 (pbk)

Amazon, hardback, £26.39 or £19.99 paperback.