Dartington Hall and Old Church Tower, Devon

The buildings visible today around the Great Hall on the Dartington estate can be dated to all centuries from the 14th to the 20th. This recording exercise has concentrated primarily on the medieval buildings, but has taken account of all periods of graffiti and the phases of building on which they occur.

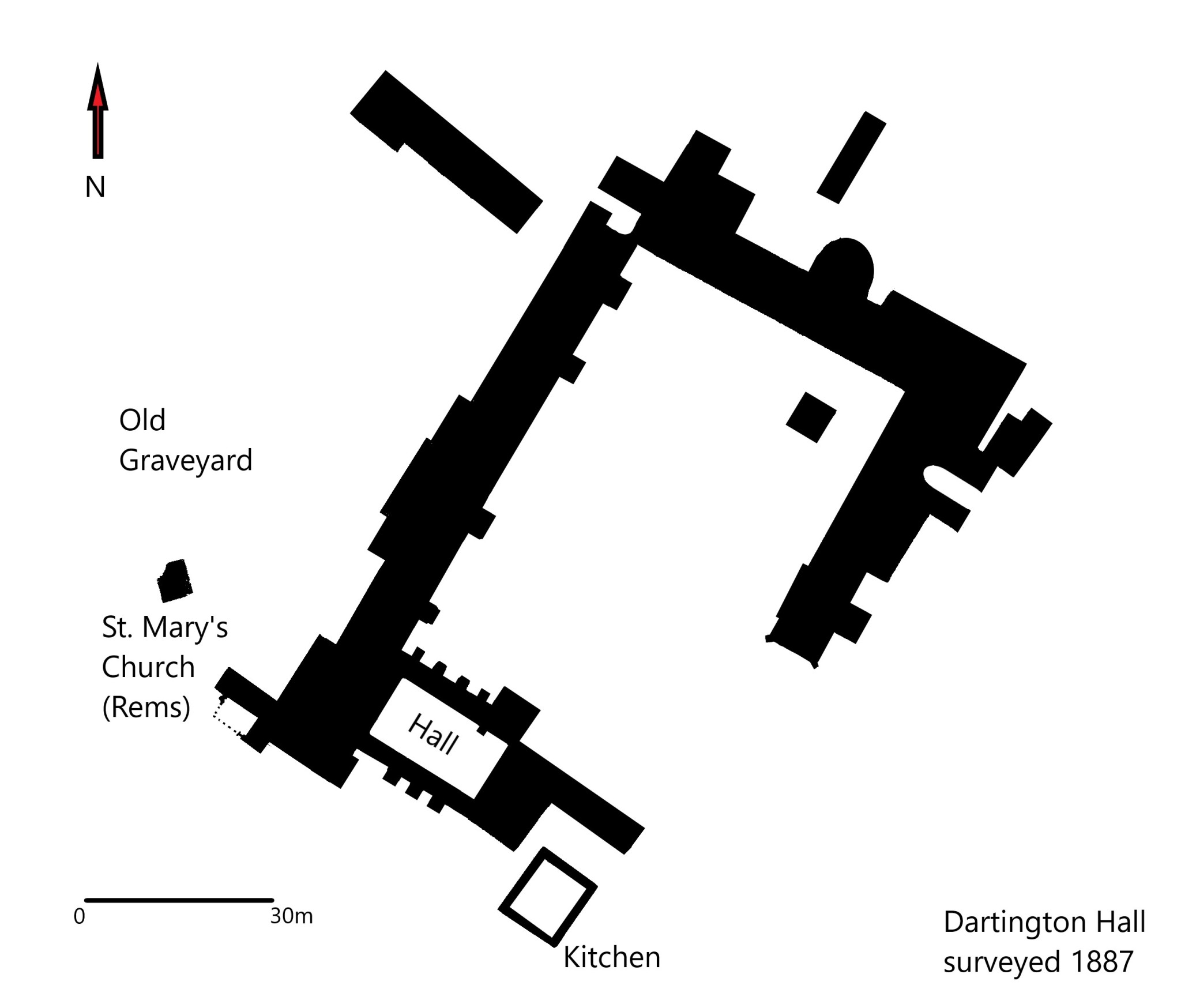

Dartington Hall was developed by John Holland, the 14th century landowner. Dartington manor was first recorded in the ninth century and was later listed in the Domesday book; the administrative centre and the early Hall is understood to have been on this site, slightly to the south of the current buildings and adjacent to the now demolished church of St Mary.

The owner of Dartington recorded in the Domesday book was William de Falaise, a follower of William of Normandy who supplanted the Saxon Alwine. His stepson, Robert Martin, inherited Dartington around 1107. The Martin family developed the deer park and a residence there, but by 1386 the estate had passed back to the crown and the Martin buildings on the site were in ruins. The estate was subsequently granted by Richard II to his half-brother John Holland, Earl of Huntingdon and first Duke of Exeter, who was also a great grandson of Edward I through his mother’s family.

John Holland married Elizabeth, the cousin of Richard II, daughter of John of Gaunt and sister of the future Henry IV. The network of royal connections and the patronage of his half-brother, to whom he remained firmly loyal, probably goes to explain the massive redevelopment and palatial scope of the medieval buildings by John Holland at Dartington. It also led to the downfall of John Holland who, following the murder of Richard II, was involved in a brief and unsuccessful rebellion against Henry IV and executed, leaving his plans for the completion and aggrandisement of his huge north courtyard unfinished. The fact that the remaining buildings remained within his family was a result of the efforts of his widow Elizabeth to keep Dartington as a home for their children.

The Holland family continued their occupation of Dartington until the death of the fourth Duke in 1475, after which the estate again reverted to the Crown. It was owned from 1487-1509 by Margaret Beaufort, mother of Henry VII and then from 1525-1539 by Henry Courtney, Earl of Devon, being surrendered on his execution for treason.

Finally in 1559 the estate was sold to Arthur Champernowne, whose family managed to remain in possession, with some degree of luxury apparent in the surviving rooms of the Georgian period, until 1925 when they sold it to Leonard and Dorothy Elmhirst, who undertook the task of restoring the medieval buildings and of building new accommodation for the Dartington Hall Trust. The Holland buildings had already been altered by the Champernownes: in 1560-1 and again during the 17th century, when three ranges of buildings to the south of the current hall were demolished and altered yet again in 1740.

The estate had become a largely agricultural concern by the mid 19th century. Many of the older buildings were completely derelict; others had become dilapidated and many were altered for farm use. The roof of John Holland’s Great Hall in particular had caused so much alarm that it was deliberately removed in 1813. The Church of St Mary, which had stood behind the west range of the North Courtyard, was removed in 1878-1880 to a new site by the main road past the estate, leaving the graveyard and the tower, which still stands, with a number of Champernowne tombs resited in its base.

The 20th century work was sympathetic and has earned its architect, William Weir, many plaudits but a consequence of the extensive restoration has been that large parts of the original fabric have been replaced with new stone and timber, while surviving internal walls have in general been heavily overpainted.

(note: the mason’s marks recorded at Dartington during restoration are shown at the end of this report)

Graffiti in the original tower of St Mary.

The remains of St Mary’s church at Dartington Hall today comprises a tall plain tower of rendered stone rubble with granite coping and string course. The original building is thought to have been 13th century, with the top stage being later, possibly 15th century. The church was possibly founded by the Martins in the 13th century as a rural oratory on their manor. Sir Nicholas Fitzmartin was the patron on the first rector in 1261.

Internally the tower stone stairs survive to the first floor after which there are modern steel ladders through a steel checkerplate second floor and up to the roof. The doors at the entrance to the tower and on the first floor appear to be of some age and could well be contemporary. The leaded roof is a relatively new installation and has no visible graffiti. The stonework around the parapet is too heavily encrusted with lichen for any potential marks to be visible. As all the tower window and louvre openings have been closed internally with rigid acrylic sheet it was not possible to examine every surface. A burn mark was recorded at the top of the second floor door, although not of the usual taper burn shape. A series of linear score marks, not all related to stone mason’s laying out, along with a mark loosely resembling a letter H with two cross bars was noted on the south side of the east facing window on the second floor. Initials (WT, DE) were recorded on the stone centre pole just inside the entrance door along with a date, 1899, and a possible very eroded H. A capital P and a W were recorded on the lower door, not apparently related to each other.

Clock Tower

At the east end of the Great hall there is a large 3-storey entrance porch and clock tower with moulded pointed door arch, a polygonal stair turret in left angle and an 18th century bellcote on the roof.

The tower is accessed internally via the northernmost of four doors in the screens passage across the rear of the Hall. Inside the lower stairs door, close to the door frame, a small collection of graffiti was found.

Upper Solar

Adjacent to the lower tower room there is access to the Upper Solar, used in the 1970s as a sitting room, now used as a teaching and presentation room. The stone window mullions appear to be relatively new work, but a stone cupboard surround in the western wall carries fairly extensive graffiti on its northern splay.

Solar

On the floor below, apparently a sitting room in the Elmhirst’s time and now used as part of the refectory, the room has a large fireplace, heavily overpainted and carrying no visible signs of graffiti and a heavy chest with linen fold panelling, visible in post 1925 photographs of the room, which was at that point used as a sitting room. The chest is severely burned in several areas on its lid, probably as a result of hot vessels being placed on it, however there are signs of taper burn marks on the linen fold panels.

Graffiti on the main hall Clock Tower roof

The roof of the clock tower is entirely leaded, with a free standing bell cote installed by Arthur Champernowne in 1741. The bell itself dates to 1737. A nineteenth century engraving by Daniel Prout indicates damage to the finial, but the bellcote as it survives may well be principally 18th century leadwork, although with modern bracing on the legs. The clock in this building has one large face on the top storey of the north elevation and the boxed-in works descending in part to the room below.

There were no obviously intentional internal marks surviving on the upper floors of this block and the stair post had been heavily gloss painted in the past. The leaded bell-cote or cupola, however, presented an extreme example of the ‘palimpsest’ effect of repeated inscription over many years. It is not clear how old the present leading is, although it clearly pre-dates the Elmhirst renovations as the earliest date so far deciphered is 1880. So deep is the overlay, and so dense the mesh of superimposed names that decipherment is extremely difficult. The good preservation of dates from the late 19th century tends to support the idea that the leading is original, with the more deeply buried and more obscure inscriptions going back a further 140 years. It would appear that the soft lead of the cupola was far preferable to any stone window or door frame.

There are a number of wartime dates including some from US servicemen, thousands of whom were stationed in South Devon in preparation for D-Day. Of especial interest is the name ‘John Crook’ which appears once and also ‘J. Crook’ which appears twice, once with what appears to be a service number. Further research is required but it is known that Frank Crook was farm bailiff at Dartington at this time and that a John Crook appears in the Dartington Hall newsletters of the period on more than one occasion. Initial investigation of local birth registrations show a John Crook registered as son of a Frank Crook in 1923. No relationship is completely certain as yet, but there seems a strong likelihood of a family connection.

Kitchen area

The lower door to the clock tower staircase exits into the screens passage, which runs the total width of the building and separates the Great Hall from the service area. The huge, formerly detached, kitchen, accessed via the central of three service arches, was a ruin when the estate was bought by the Elmhirsts and might have remained so, but the Hall itself was found sufficiently useful for the kitchen to be rebuilt and returned to something of its former use as a refectory, now renamed the White Hart, in commemoration of the distant link with Richard II. The kitchen was checked for graffiti, but the extent of the rebuilding and redecoration, combined with its once ruinous state, seem to have obliterated anything that might have been there.

Door arches in cross passage

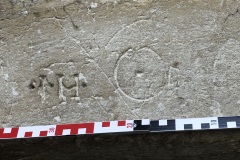

The cross passage to the rear of the Hall has four door arches, one to the tower stairs, and the other three the standard medieval service arches typical of the traditional Great Hall layout. The wooden screen separating the passage from the Hall is a modern replacement. All four arches are scratched with graffiti and none has been overpainted. Given that this was the access to the huge detached kitchen it is interesting to note that few of the marks appear to be apotropaic. Of especial interest is a small piece of script (undeciphered as yet) and a small shield bearing the Champernowne arms, identifiable from the shields on the surviving tombs in the church tower.

The Great Hall.

The great Hall as seen today has a large original stone fireplace and doorways to the west (fireplace) end. The original stonework of the fire and the southern door is Beer stone, a hard chalk from East Devon, ideal for fine carving and perfect for graffiti scratching. The huge gothic stone window mullions are in the harder oolitic limestone and are a mid-18th century replacement of a late 16th century set of windows, which in turn replaced John Holland’s original tracery. The window splays were cut back to let in more light, so any earlier graffiti in that area would probably have been eradicated at that point. The sill levels have also been changed. The glass in the windows was inserted in 1932 when the building was restored. Severe water damage from the period when the building was roofless has affected much of the doorway in the south wall of the hall, and shows slighter effects on the doorway in the west wall. The window mullions appear to have suffered the least, however no graffiti was visible on any of these surfaces. The hall fireplace, however, had a long spread of graffiti from end to end, across the fine stone surround and also on the blocks above, which would originally have been plastered and limewashed and on blocks within the fireplace itself, some of which are mason’s marks. The door to the north of the fireplace leads to the suite of 18th century rooms, formerly used as a private house for the Champernownes and by the Elmhirsts. The rooms were immaculately kept and showed no sign of graffiti.

North door arch

Leading from the cross passage at the rear of the Hall, the North door exits the building towards the North Court through the base of the clock tower. The arch is part of the 14th century Hall plan, and is appropriately large. The fine Beer stone mouldings show some signs of intentional graffiti as well as scarring from animal tethers from its period as a farm building.

The West Range

The lodgings in the west range, designed as part of John Holland’s seigneurial complex, would originally have provided private accommodation for visitors to his Hall. The block, which runs the full length of the North Court, joins the Hall to the entrance wing on the north side of the court. The block consists of five groups of lodgings, some with shared stone porches, which today serve as function and letting rooms for the Trust. (Please note: these rooms are not publicly accessible).

The set of lodgings adjacent to the Hall (the south end of the lodging range) consists of a single door below a built out porch, which leads today to the Elmhirst Centre. At the point at which the Elmhirst’s bought the Hall this range was largely used as animal housing. The stone surround to the door is in surprisingly good condition and despite some over painting clear marks were visible on the door head and also on the door itself. An early crossed I and an H occur together, tempting the observer to thoughts of John Holland. Examination of the other doorways in the range showed damage consistent with animal penning and then on the final arch, at the northern end of the range, a further large mark of concentric ellipses – possibly one noted during the restoration of the range.

The interiors of the lettings and meeting rooms in the range were checked, but restoration and re-ordering over the years, combined with plaster repairs and paint seem to have obscured anything that might otherwise have been found. The one exception was in the north-west corner lodging, in room 8, where a huge ship graffito takes up most of the north wall. Incised into plaster, the main ship is about 2.8 metres long, with some smaller vessels indistinctly marked around it. Various numbers and possible letters, including a single crossed I and the single clear date 1516 towards the bow of the main ship. Then uneven nature of the wall, plaster repairs and the ubiquitous overpainting – along with a confusion of superimposed rigging and ‘waves’ – make this graffito frustratingly difficult to photograph.

Interestingly the ship graffito and the other showing concentric elliptical shapes were noted during the restoration of the range. The available pictures do not add anything to those possible today, but the architectural historian, Anthony Emery, who produced an exhaustive history of the Hall in 1970, did ask the National Maritime museum for an opinion on the likely dates of the ships. Combined opinions favour an early 16th century date, which would agree with the incised date of 1516.

North entrance arch, Welcome Centre and Barn Cinema

The north side of the north court is formed of a series of buildings which were solely in use as farm buildings in 1925, when the Elmhirsts bought Dartington and which from surviving accounts seem likely to have been used in this way since at least the 17th century. The entrance arch is small and very plain considering the size and potential splendour of the Court and Hall beyond, and Emery is of the opinion that it was John Holland’s intention to build something grander, had he not fallen foul of Henry IV. The gates now closing off the courtyard from the outside world were provided by the Elmhirsts in 1928. A lower room in the range, to the west of the arch, is now used for a welcome centre and houses a single huge octagonal pillar, supported on what appears to be a later stone base which is capped with slivers of iron. Whether as an apotropaic act or simply as an attempt at damp-proofing is not clear. The post supports two huge roof timbers, which do not appear to be matched, leading Emery to suggest that the entire upper floor and the supporting post may have been taken down and reassembled – probably when the foot of the wooden post rotted out and required replacing. The pillar itself shows considerable wear and tear from contact with farm animals and is also notable for a series of clear taper burn marks, suggesting a firm intention to inoculate it against fire.

To the east of the arch the roof of the north range continues in a long line, past the end of the truncated and re-built east range, forming what was a long barn and an adjoining annex for a 19th century threshing house. There is no real dating evidence for the barn from its structure and Emery considers that it might be post-medieval although an earlier date is not impossible. The roof timbers of both structures were too high to be accessible for examination without specialist access.

The barn was converted to a theatre in 1936 when the backstage and dressing room areas were considerably rebuilt and it is currently in use as a cinema. Although the timbers in the roof were not accessible, part of the newer backstage area was highlighted by staff as containing ‘weird graffiti’ and ‘something from a mathematician gone mad’. Always pleased to record the odd and mad, the wall was inspected and proved to be formed of simple mathematical notation and formulae each inscribed on a single brick. Initial conclusions on the extremely neat chalked graffiti is that it formed an art installation possibly dating from the time of the Dartington College of Arts (1961-2010) or from the Dartington Hall School era (1925-1987). A smudged name, John Kerry, Penny or Perry, 1971, is visible in red chalk at the extreme left hand end, slightly behind some interior woodwork. It seemed a fitting conclusion for this short survey.

Dartington Hall provides a rare opportunity to see medieval graffiti in a completely secular context, even though a considerable amount has undoubtedly been lost to demolition, erosion, alterations and restoration over the centuries. The most curious fact that arises from this recording is the apparent shortage of apotropaic symbols. Even allowing for the loss of the window splays in the Great Hall, the lack of evidence in the screens passage alone is remarkable. It is highly likely that the once detached kitchen was the most protected area and that its derelict state in the 19th century, coupled with its total restoration in the early 20th, caused the loss of all of it, but that can only be a conjecture. The fact that generations of occupants and visitors have inscribed mementoes of themselves certainly makes it clear that there was no lack of people happy to write on the wall, merely that they seemed not to feel too much need for supernatural protection.

Dartington Hall is a remarkable survival of a high-status secular medieval house. Semi-derelict, decaying and already partially ruined by the 1920s it was saved only by the timely arrival of Leonard and Dorothy Elmhirst. It is well worth visiting, even for those not collecting graffiti. Today it carries on as a centre for education, sustainability and the arts and in consequence even the more obviously accessible of the locations visited are not necessarily open to the public at all times. Neither tower is publicly accessible at any time. Please consult the Dartington Trust website for opening details and check with the Welcome Centre desk for events using the Great Hall.

Acknowledgements:

With many thanks to everyone at Dartington who has been so universally kind and helpful, especially: Alison Jackson-Bass, who first alerted Raking Light to the importance of the site; Jacqui Hunt and Sandra Vincent who organised access and supplied all the risk assessments and Nick Harris who unlocked the towers and provided an escort to their dangerous heights.

Photographs by Anthea Hawdon & Rebecca Ireland, Report by Rebecca Ireland

Selected Bbliography:

Cherry, B & Pevsner, N. 2004, The Buildings of England: Devon pp.308-320 Yale UP NewHaven & London

Emery, A. 1970, Dartington Hall Clarendon Press, Oxford

Gray, Todd. 2003, Lost Devon pp.69-70 Mint Press, Exeter

Lysons, D. & Lysons, S. 1806, Magna Brittanica; being a concise topographical account of the several counties of Great Britain Vol 6, p. cccxlix; p. 152 Cadell & Davies London

Prout, Samuel. 1812, Picturesque Delineations in the Counties of Devon and Cornwall T. Palser, London

W.G.Hoskins, W.G. 1972, Devon pp. 381-382 David and Charles

Williams, Ann & Martin,G.H. (ed) 1992, Domesday Book p. 315 Alecto Historical editions, Penguin.

Photographs by Anthea Hawdon & Rebecca Ireland, Report by Rebecca Ireland

Dartington Hall,

Dartington,

Totnes,

Devon,

TQ9 6EL

Search terms: WT,DE,P,W,IM,EC, saltire, cross, WW2, signatures, flags, shield, regiment, Crossed I, 1924, Whittaker, Harris, John Flower, 1880, Hudson, Bolton, 1944, Parnell, Johns, 1921, face, horse, Sheila Mackenzie, A Hapgood,WH Manley, 1932, JM,TO, 1935, 1966, P Gipson, 21.7.34, Amy Harvey, Hilda Boyd, Tim Costello, 1991, True Love, Sybil, Frank, Heart with arrow, Heart, Ailsie, Norman, Barry, Muller, 1885, T Holland, 1880, M, script, date, dates, FB,CL, V Hext, taper burn, burn mark, AUG, SR, CP,H, AC, RE, butterfly, X, Lombardic A, arrowhead,W, score marks,tally, mason’s mark, star, grooves, 1639, IM,ED, concentric circles, IH, holes, ship, ships, rigging, flag, 1516, formulae.