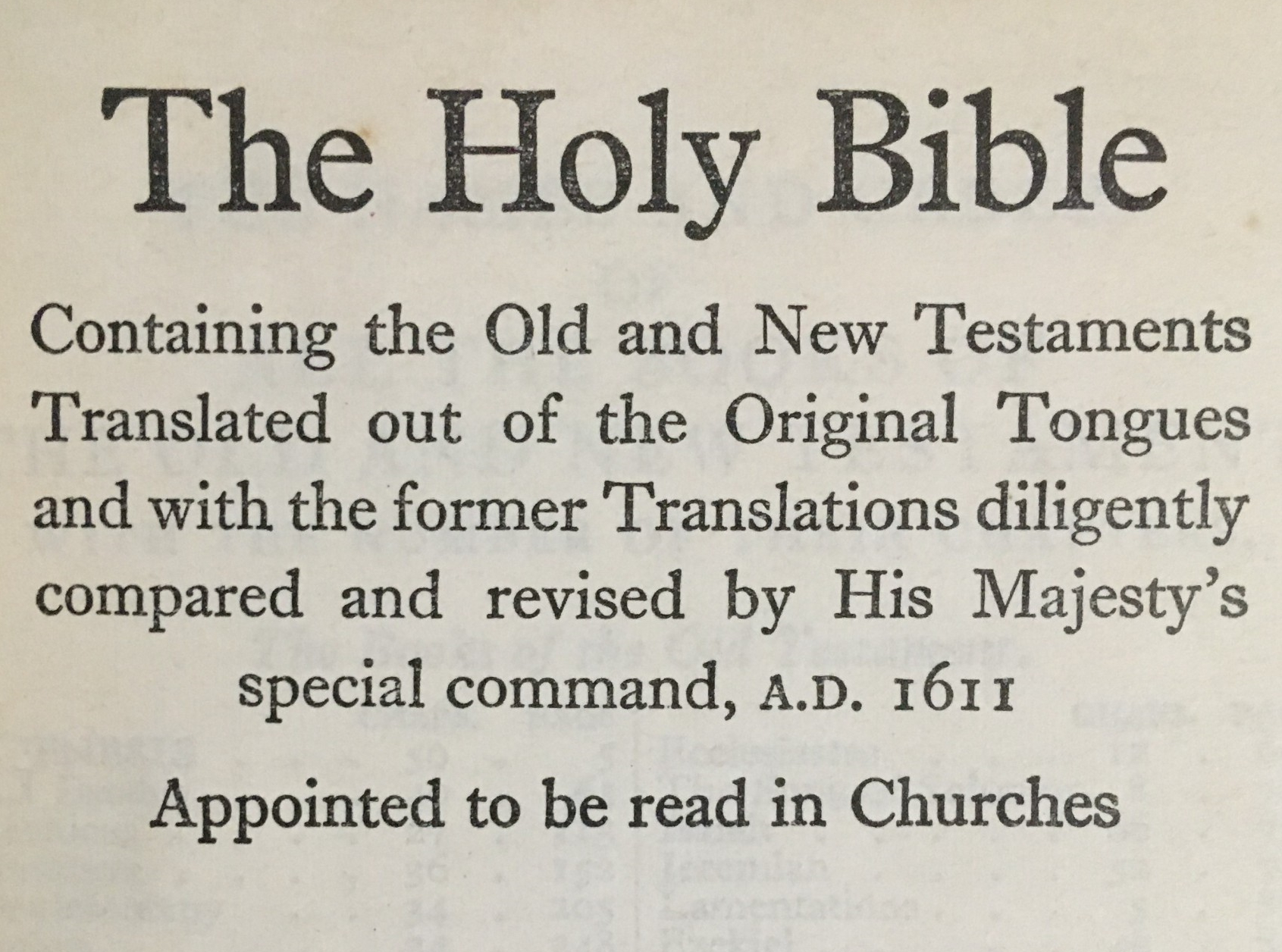

Begun in 1604 and published in 1611, the King James Version became the Authorised Version of the Bible, and has never been out of print. Rebecca Ireland looks at it in the context of the study of magic and folklore.

This monumental work of translation and refinement of all the Biblical texts known to exist in the early modern period was the work of a team of some 47 scholars, convened by King James I of England (VI of Scotland). It may seem an incongruous inclusion in a reference shelf devoted to magic and folk belief, however, the long span of its influence in British society, coupled with its increasing availability as printing processes evolved, means that it became the go-to text for those wishing to predict, cure or conjure with a nuance of scriptural authority.

Latin phrases, some extracted from the liturgy, had been a natural part of folk magic in the Catholic centuries, and some had clearly existed for generations – often suffering debasement, over time, into a form of gibberish. Latin in spells and charms persisted into the early modern period, even after its banishment from church services. James Device, one of the ten Pendle witches (hanged 1612) gave a charm in Latin as part of his confession: ‘Crucifixus hoc signum vitam eternam. Amen’ . This would apparently procure the user a drink within an hour. However, it was the new, comprehensible, power of the Authorised Version that eventually gained ascendency in magic as much as in conventional religious life.

Prior to the convening of the 47 or so scholars, there had been a number of versions of the Bible in English. The earliest was that produced in about 1384 by John Wyclif and his collaborators. This was effectively a translation of the Latin Vulgate of St Jerome, created in the late fourth century CE, which itself was a translation of earlier Greek and Hebrew texts. Jerome’s Latin text was created in order to provide a standard Bible, suitable for use across the Catholic world. The aim of Wyclif and his followers was to do exactly the same, but in their own language, accessible to all who could understand English. Unfortunately for many of them, producing a Bible that was not approved by the Pope and which might be read by any literate (as distinct from Classically educated) English speaker, was an act of heresy punishable by death. The common people were not thought capable of comprehending the Word of God, nor should they attempt it in case they committed an appalling heresy that might result in damnation for all. Besides, the cynical modern mind asks, who could exercise control over a people who believed they had direct contact with the Divine? The fact that the Bible was in Latin, and was, as yet, still hand copied, was a proper protection for all.

The first English version of the scriptures made by direct translation from the original Hebrew and Greek (with some reference to Luther and Erasmus) was the work of William Tyndale of Gloucestershire. He was accused of wilfully perverting the meaning of the scriptures, and his New Testaments were ordered to be burned as ‘untrue translations’. Tyndale’s own words were: “I defie the Pope and all his lawes. If God spare my life, ere many yeares I wyl cause a boy that driveth the plough to know more of the Scripture, than he doust.” Clearly a dangerously radical line to take. Despite working in secret, moving regularly around the English mainland, and spending much of his working life on the continent, Tyndale was finally betrayed and executed in Belgium in 1536.

Tyndale’s work, however, lived on, providing not only the first printed English bible, but the impetus for a whole series of translations during the sixteenth century, as Protestantism gained ground in Europe. Indeed, such was the call for accessible texts, and such the ease of publication once printing became a feature of life, that even a Catholic translation of the Latin Vulgate was produced, in 1582, at Rheims, by Roman Catholic scholars.

The translators who made the King James Version took into account all of the previous versions, and comparison shows that it owes something to each of them. It owes most, especially in the New Testament, to Tyndale.

The King James Bible, soon to be the Authorised Version (that is, authorised for use in church) became the standard text. This was the version that prevailed in churches, schools and families. Later translations (quite as many as the translations that precede it) may be easier on the modern eye, their cadences better suited to the modern idiom, but this is the Bible that was used for divination, curing and folk magic across the country in the post medieval and modern periods.

So, to what uses can the Bible be put in our context?

The bone knit verses: Ezekiel, Chapter 37, verses 1-14, tells the story of the knitting together of the bones, ‘bone to his bone’, in the valley of dry bones. This is the source of the Spiritual ‘Dem Dry Bones’ (first recorded 1928), and has also been the source of a vast number of folk remedies for bone healing. The oldest vernacular cure so far recorded comes from Germany (in Old High German, not Latin) around the 10th century. Recite over the injury: ‘Fletch to fletch and bone to bone, sinew to sinew, skin to skin, blood to blood, air to air, each one in your place. In the name of the Father Son and Holy Ghost, Amen’.

Turning the key/Bible and key: There are three versions of this charm. One, to discover a lover’s name; two, to find the name of a thief and three, to remove a spell. You will need a substantial old fashioned key. British Standard latches have no place here.

– To discover your lover: place the key on Ruth, Chapter 1, verse 15: ‘whither thou goest, I will go’. Close the book, with the bow end of the key protruding, and tie it up. Two people support the whole arrangement, with fingers under the protruding loop of key, and the key will turn when the name of the lover is mentioned.

– To find a thief: this time, use Psalm 50. A gloomy rant of a psalm, which declares deliverance for the righteous and a threat of tearing to pieces of the thief, adulterer and slanderer. In order to discover a thief a key is laid in the book, against the psalm. The book is bound shut. The book is then suspended by a cord and the names of the suspects read out. When the correct name is read the Bible and key will spin.

– To remove a spell: place the key on two crossed sticks, one of Mountain Ash and one of Yew. Place sticks and key on Ephesians, Chapter 6, verses 13,14,15: ‘take unto you the whole armour of God…’ the verses to be read aloud nine times. At each repetition a small tear is made in a piece of white paper. To break the spell, the paper should be folded up and sewn into the clothing of the person bewitched without their knowledge.

Toothache/ague cure: read John, Chapter 9 (the curing of the blind man) and Exodus Chapter 12 (the story of the first Passover) this, in line with the bone knit verses, has a long history, and variants of the cure, loosely based on the verses from John, occur in many folklore collections.

These are the tip of an iceberg of near forgotten Bible superstitions, many of which will have been commonplace when the King James Bible was part of almost every household’s chattels. There must be more to be recovered. The book itself is a significant part of the social history of these islands, and should be regarded as a necessary reference in any library of esoteric studies.

The King James Bible is readily available from all large booksellers. A traditional leather-bound hardback version can be found on Amazon, publisher: Collins, Box Lea edition, 2011. ISBN: 9780007259762 £12.93. A Kindle version is available for 99p. A free online resource exists here.

Reviewed by Rebecca Ireland.