Magic in Medieval Manuscripts, Sophie Page, 2004; expanded hardback edition by British Library 2017.

Small but perfectly formed: this books is a little jewel to brighten the dark January evenings.

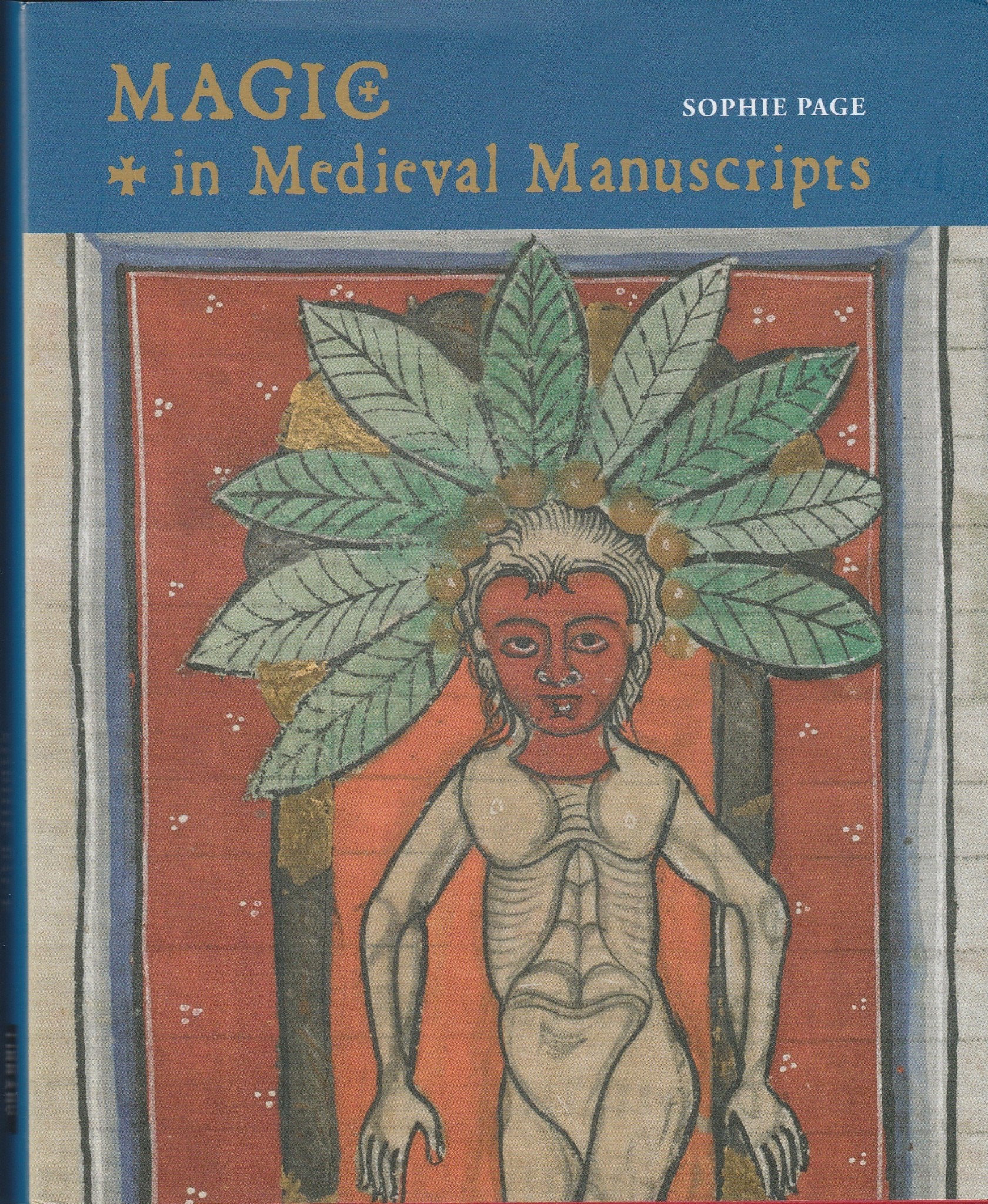

This is not a manual of spells and charms, though a number are included, nor is it simply a picture book, though the illustrations are excellent. It is, rather, a very concise scholarly exploration of magic in the medieval world, and the responses it elicited.

Originally a 64 page pamphlet, with small illustrations, Magic in Medieval Manuscripts was re-released in an expanded format in 2017, to coincide with the exhibition ‘Harry Potter; a History of Magic’. The book understandably highlights items such as the uses of mandrakes and on gathering herbs, such as basilica; considered to be a protection from Basilisks (12th century). This herb should be sprinkled with spring water, and oak leaves should be shaken over it. At sunset the practitioner should invoke the earth, commencing ‘O Holy Goddess Earth…’ Once picked, the herb should be ‘encircled with gold, silver, ivory, boar’s tusk, a bull’s horn and honeyed fruits of the earth’ in order to preserve its powerful properties. Despite a solid medieval date for the record of this charm, the pagan overtone of the invocation is unmistakable, and in consequence it was excised from many contemporary collections of magical formulae – despite the admitted advantages of it as a source of protection from the deadly basilisk family.

A number of the illustrations show ritual diagrams or magical symbols – undoubtedly of use to graffiti collectors eager to enlarge their vocabulary of magical signs. Within the text we glean information not merely on complete spells and charms but also on such arcane details as the popularity of the hoopoe. This exotic bird, all parts of which might be used in magic, was also often portrayed as a companion of the Virgin Mary and generally looked rather like a parrot, which may well tie in with a number of finds of lead-tin alloy badges from medieval archaeological contexts, also portraying a parrot-like bird.

Should you wish to see the charm for a cloak of invisibility it is of course included: facing page 98.

The content is historically accurate and elegantly framed – the association of the new edition may be with a publication originally aimed at children, but the material is not childish. References include the Picatrix and the Ars Notoria, as well as modern texts by such recognised scholars as Richard Kieckhefer.

I am wary of describing this book as lavishly illustrated: the expression I adopt myself on reading those words tends to be that of slitty-eyed suspicion, combined with a cynical conviction that six leprous half tones is about as lavish as the average publisher will want to be with the design budget. In this case, however, the British Library have really done their author proud. More than half of the 128 pages are high quality full-colour reproductions of manuscripts, or parts of manuscripts, held by the BL.

Everything is printed on good quality stock, and the endpapers even have a burnished bronze/gold finish. It may be too late to get this book for Christmas 2019, but it might well be worth putting it on the birthday list.

Available online from Waterstones for 12.99; or from the British Library online shop (a slightly more complicated experience, and so not given first mention). It’s also available on amazon.uk

Publisher: British Library Publishing 2017

ISBN: 9780712352055

Edition: 2nd Revised edition