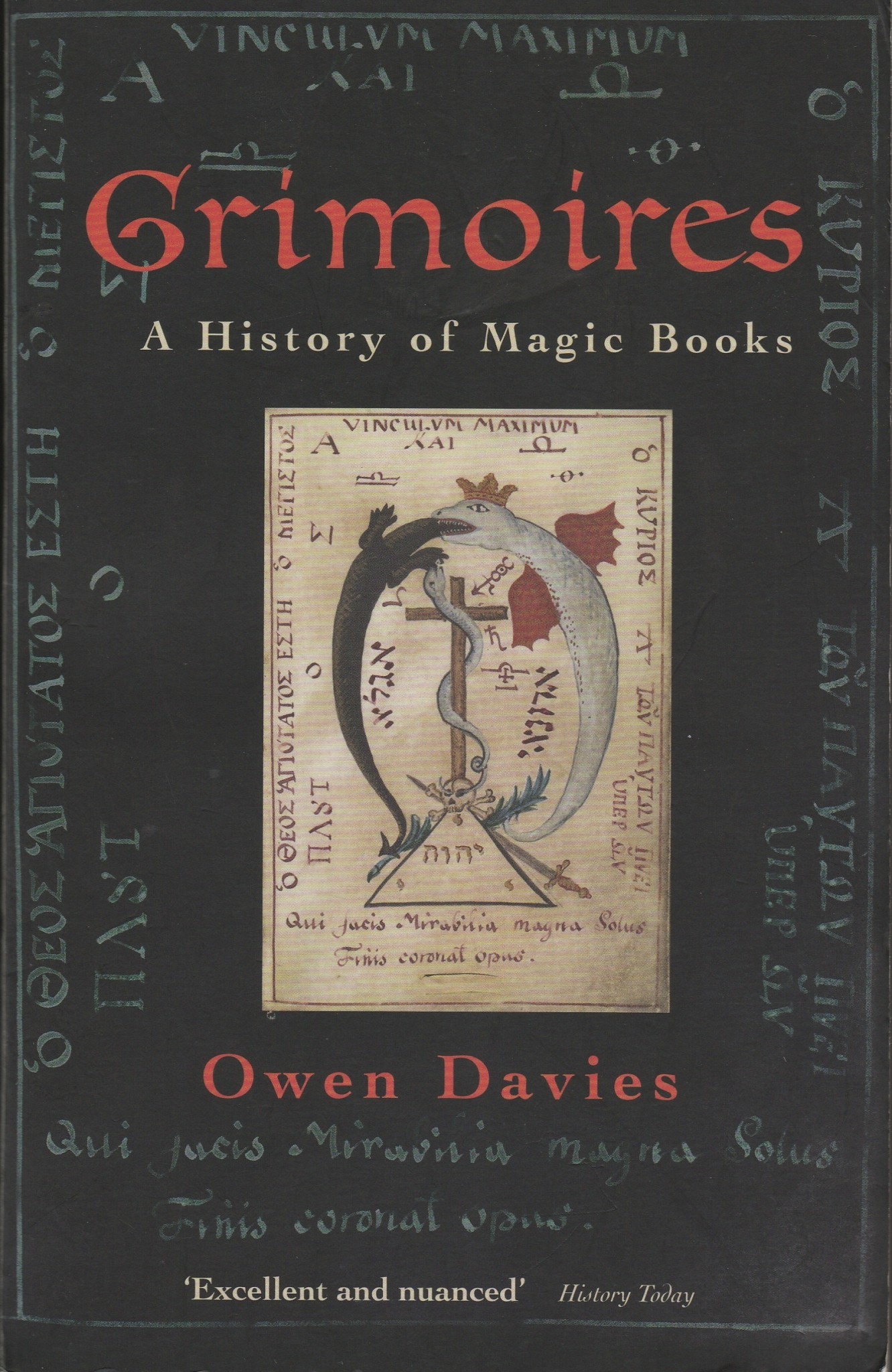

Grimoires, A History of Magic Books. Owen Davies, OUP 2009.

Grimoires, A History of Magic Books. Owen Davies, OUP 2009.

‘…for many down the millennia and across the globe no books have been more feared than grimoires.’

Thus Owen Davies introduces his exhaustive history of Magic Books, a complex and extensive survey of what, once one begins to pursue it, seems an endless road. That is not to say that the book is tiring to read – far from it – but that the subject, contrary to what one might have believed about the rarity and exclusivity of Grimoires, is simply vast. Not only specifically ‘magical’ books could fall into the category: anything thought to reveal a magical procedure or potential instructions for a spell or charm might be pressed into service. The Bible, parts of the liturgy, mass produced fortune telling books, Alchemical texts intended for the enlightenment of educated gentlemen and even Reginald Scot’s anti-witch belief book The Discoverie of Witchcraft. It seems that almost anything could be pressed into service as a magical fragment. The mass production, reproduction, sale and dealing of Grimoires appears to have been secretive, but ubiquitous.

Commencing in antiquity, with the tradition of wise men from the east (whether in threes or not – although three itself is a magical number) the first chapters document the arrival of eastern esoteric ideas, whether correctly understood or not, in the western European world. The book proceeds through the European reformation; its assorted schisms, wars and deep suspicions accompanied by swift persecution of any ‘unorthodox’ practice – regardless of the orthodoxy concerned. Religious war encompassed minority and occult beliefs, as well as the mainstream. The danger from the grimoire was a physical reality, aside from any spiritual concerns that might have assailed the timid.

And yet, throughout the centuries of religious upheaval, when the danger inherent in owning a grimoire was at its highest, production flourished and ownership increased.

European magical texts got to the New World nearly a century before the Pilgrim Fathers: ‘the doctor Cristobal Mendez, tried for sorcery before the Mexican Inquisition in 1538, testified that he had learned the art of making silver and gold astrological medallions … from a book he had read in the cathedral library in Mexico city.’ Cheap magical chapbooks were imported into America from Britain and the rest of Europe in the following centuries but, following the War of Independence, American production took off and grimoires developed a mass market presence that left old world production standing.

The dangerous nature of the books has of course been the major reason for their concealment: if you are going to lose your body parts, and potentially your life, for owning a certain book, you are surely not going to publicise that you have it. What is astonishing, considering the risks involved at many points in history, is the industrial level of their replication revealed by this study. Even in pre-print days it would appear that everyone with a degree of literacy who wanted a grimoire could get one, even if it meant making their own handwritten copy of a borrowed book. Indeed, making a handwritten copy was preferred; hand copying imbued, or perhaps conveyed, a special power. Those who were less literate, or even illiterate but observant, would still utilise literary fragments from the books to create charms and spells for clients. Once print and literacy began to spread across the globe, mass produced grimoires were right there, fulfilling a market demand.

This is a remarkable book, not just for its historical scope but also for its geographical spread, and its thoroughness serves to highlight the huge range and popularity of grimoires across the centuries, despite their covert nature. I was reminded of a hackneyed archaeological motto: absence of evidence is not evidence of absence. In this case it could not be more true, and once Owen Davies gets digging, what evidence he uncovers.

The huge breadth and depth of this book and the vast literary underworld that it explores means that it is not a swift read. There are no quick fixes; no snappy soundbites. Even in paperback the body of the text runs to 283 close-printed pages (kudos to the OUP for using a particularly clear and user-friendly font). The notes and further reading suggestions run to another 77. This is the only drawback, and only then if you don’t like your scholarship densely packed and as full of good things as Christmas pudding. It is an essential part of any bookshelf devoted to the esoteric, and I absolutely recommend that even the timid reader engage with it as a project: there is a huge amount of fascinating information waiting for you here, and all of it well and clearly expressed. Take your time and immerse yourself.

Review by Rebecca Ireland

Paperback 2010: 368 pages, £12.67 Amazon

Kindle edition, £11.39, Amazon

ISBN 978-0-19-959004-9 (Pbk)