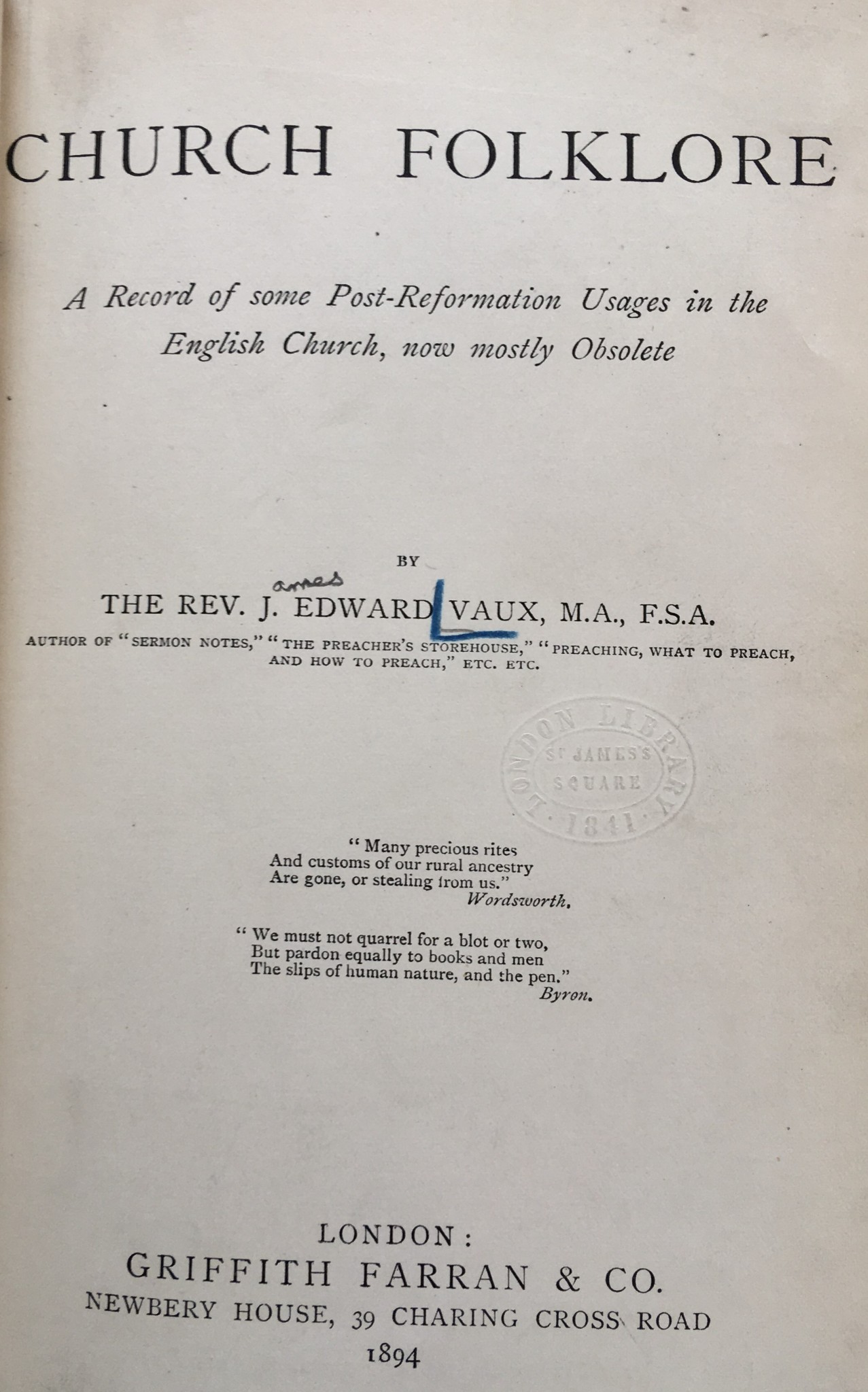

Church Folklore

Church Folklore, A Record of some Post-Reformation Usages in the English Church, now mostly Obsolete.

The Rev James Edward Vaux M.A., F.S.A

Griffith Farran & Co. London 1894

‘When we search into the religious records of the past we cannot help being, at times, painfully struck with what appears to us a gross disregard to the sacredness of the consecrated buildings in which our forefathers assembled for worship’.

The words of a pious, late Victorian clergyman, most of which we might well disregard in our hunt for the undoubtedly impious scratchings of graffiti on the walls. However (and it is a useful however), the point about J.E.Vaux, across whose work I stumbled while looking for an entirely different reference, is that he was exactly that: a pious late Victorian. He gives us, first hand and in an entirely readable format, a small insight into the front end of late Victorian Anglicanism.

That is not to say that he rants about the perceived shortcomings of his predecessors – he merely records them, notes that they may be ‘utterly at variance with our modern ideas of reverence’ and moves on, usually to reference a discussion with another clergyman on the same topic. It is the awareness of the ideas of 1894 as both ‘modern’ and different and the fact that clearly many of Vaux’s contacts felt the same, that makes this book a useful curiosity.

Vaux himself was surprised by the sheer volume of the subject on which he had embarked and apologised in the preface about the size of the book – ‘the extent of the subject was unknown to me. It was arranged with the publishers that the book might be but small in size that its price might suit the general body of church folk…. The very large quantity of matter which came to hand has rendered the task of selection somewhat puzzling. This difficulty has been but imperfectly met’. He concludes with a request for more material to be provided by his audience so that a second and amplified edition might be produced.

A researcher after our own hearts. One wonders at this point what he would think of the huge output of writing on church graffiti and apotropaic practices generally that has appeared in the past decade.

Undaunted and with a slightly less circuitous approach, he launches into a well-organised attempt to document the practices he has discovered.

Starting with the use of Old St. Paul’s as a thoroughfare and place of trade and assignation, through the use of the majority of English church buildings as the local public space – court house, trading station and entertainment hall combined – he moves through uses of the church fabric previously unfamiliar to a worthy Victorian priest, though not, one suspects, all of his flock, some of whose folk and family memories might have held very different ideas. It should be borne in mind that Sunday was, until the early 20th century, the only full day off in the week. Working people were going to make the most of that.

Vaux notes that ‘even Henry VIII with all his persistent energy…was unable to check the prevailing licence’. Curiously, the profane use of the sacred space seems never to have been an issue in the countryside, despite a lingering feeling (probably by the fortunate who could move graciously from big house to big house for a ‘Friday to Monday’ and who generally wrote the rules) that it should have been. It is an attitude that persists. I was earnestly informed around the turn of the millennium, that a country church I was recording would in the past have been ‘too sacred’ for any revelling inside (the occasion was a post-concert wine and cheese – probably the millennial equivalent of a Church Ale). This despite extensive church records indicating that this was exactly what had happened, along with a church owned Malthouse outside to provide an income and some of the ingredients and a complaint to the Bishop about a priest misbehaving during a ‘cushion game’. My interrogator on this occasion was an American historian. Perhaps they did things differently there.

Moving on to the church services, Vaux mentions two ‘once familiar’ practices: daily services and one which was new to me – the ‘old custom of separating the sexes when worshipping in church’ which ’still prevails in certain rural parishes’. Certainly the vicar of Thaxted, Essex, wrote to Vaux in 1873 saying that it was ‘almost universal’. Is this reflected in the types of graffiti found in specific church locations? Or does the added fact that pre-Reformation churches rarely had seating, combined with the use of the church as a public space, mean that gendered graffiti was not limited to the place where its creator stood and knelt during services? I wish that Vaux had gone further in his exposition.

The round-up of the volume, after chapters on church decorating, high days and holy days and the unsurprising Holy wells, is a summary of surviving Heathen Practices. I rubbed my bony hands at sight of that. Devonshire lamb roasts formed the backbone of the chapter. At Kingsteignton there is to this day (modern plagues permitting) a communal lamb roast and associated fair or revel. Vaux records a similar event at Holne, though the revel there has not had a lamb roast recently. Both events seem to go back a fair distance in time, both claim a pagan sacrificial root. A more convincingly ancient ‘charm against murrain’ comes from a correspondent in Moray who in 1879 recorded a cow being buried alive to save the rest of the herd. Similar practices are reported from Cornwall ‘almost to the present day’. No singing, no dancing, no summer revel – practical magic. Similarly the collection of chips of stone from sacred statues in order to make medicines. A man is mentioned to have walked from Teignmouth to Exeter, a distance of about 18miles, in order to throw stones at the figures on the west front until he broke off a piece. Not just for the fun of casual iconoclasm, but because the ground stone, mixed with lard, made an ointment for sores called ‘Peter’s stone’ – St. Peter being the patron of Exeter.

This is a charming old fashioned read, provided with an excellent Contents section, a proper index and appendices on Church services and odd Christian names (Victorian vicars kept lists – do modern clergy have either the time or inclination?) It is not of the modern standard of folklore studies, but then Rev Vaux, when he began collecting for it, had no idea of the size of field he was entering. So far as it goes, the book does very well and its usefulness lies in its providing an educated and unbiased insight into practices which were either current or not so long gone in 1894, but which by have now become the stuff of history or, more fatally, mythology. I warmed to the Reverend Vaux and recommend his book for a little late summer reading.

Review by: Rebecca Ireland

Book available from many libraries, via JISC Library Hub