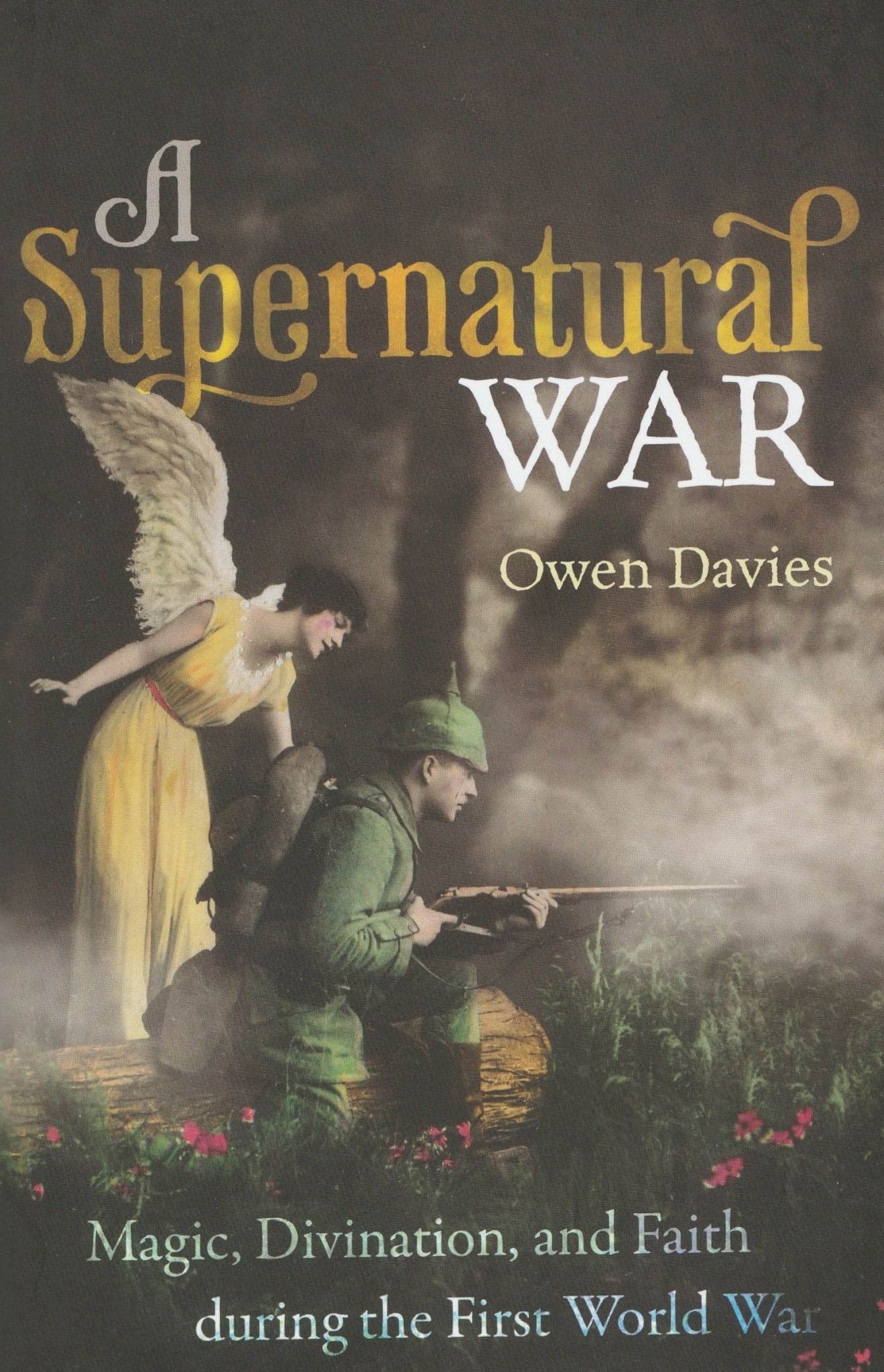

A Supernatural War: Magic, Divination, and Faith during the First World War

A Supernatural War: Magic, Divination, and Faith during the First World War

Owen Davies, Oxford University Press, 2018

Small but perfectly formed.

In keeping with the standard of publication we have come to expect from Professor Owen Davies, this is a meticulously researched and tightly written account of the range of ‘supernatural’ help sought by combatants and by their families and the wider public during the period 1914-18.

At 232 pages, plus extensive endnotes and index, it is a modest volume, but, as ever, so compacted and condensed is the information in it and so concise the language, that it is a solid slice of the social history of its period and a very satisfying read.

What was perhaps most remarkable about the Great War, from the historical point of view, was that there was, for the first time, the inclination for large scale observation and analysis of the behaviour of the people involved. Previous conflicts had naturally been recorded, their effects observed and occasionally noted, but here, for the first time, the infant discipline of psychology was applied.

Observations were more methodical, recording more accurate. What becomes immediately clear is not the disparity in the scientific approaches from all sides, but the huge variation in the amount of value placed on more traditional areas of study, and on the acceptance, or not, of continuing folk traditions – traditions which had an immediate impact on the behaviour of many of the troops and their families. In Germany, and in continental Europe generally, folk studies were well advanced and the impact of folk belief among the general population not merely accepted, but played upon to advantage in propaganda to support the war effort. In the UK little seems to have been known about any continuing folk belief and less was desired; the Folklore Society avoiding almost all mention of the conflict and concluding that people were too busy to be concerned with the resurgence of ‘superstition’ during the conflict.

The book lays out in seven succinct chapters the main areas of supernatural activity, beginning with prognostications of the war to come – which began earlier than might be imagined; the ghastly spectre of an eventual war in Europe began to manifest itself decades before the conflict finally erupted, giving a good deal of scope for prophets of doom, some of whom were bound to strike lucky. Closer to the start of hostilities, and escalating wildly once battle commenced, fortune tellers and psychics joined the fray as desperate families sought comfort and news.

Battlefield visions, spectral figures and spirit comforters form another section of study. Angels and heavenly crosses were reported by all sides; the desperate need for some form of spiritual support and salvation in the midst of the soulless horror of the first mechanised war must have been overwhelming. Curiously there is no mention of trench graffiti. Had the old apotropaic symbols lost potency by now? Had they been forgotten? Or, more tantalising, were they such ephemeral traces, upon so insubstantial a fabric, that in the perpetual destruction and rebuilding and final demolition of battlefield structures nothing has survived to be recorded?

The proliferation of mass produced lucky charms is a perhaps the most novel aspect of the First World War. The religious of course might openly carry the symbols of their faith. Soldiers not wishing to engage openly with symbols and talismans might be fooled into taking protection with them by means of amulets sewn secretly into their clothes – an age old activity for those wishing to influence or protect another with a charm.

Other combatants in other conflicts must have used mass produced tokens: stamped out religious medals and lucky charms must have been available: like the innumerable pieces of ‘True Cross’, which according to John Calvin ‘might have filled a ship’, there will have been an industry in producing them, but it was at the start of the 20th century that the industry became big business. Publicly visible and openly aware of the needs of that public, to which it was happy (indeed delighted) to cater. Jewellers in the UK and across Europe became occupied with making suitable small charms for loved ones in whatever form was currently in vogue. The number of swastika charms, for instance, might surprise the reader now, with the hindsight of World War 2, but in the First World War the swastika was hugely popular as a lucky charm in all manner of contexts. Charms might also be entirely invented by the manufacturer of small goods: a variety of small wooden-headed charms, collectively referred to as ‘touchwoods’, were manufactured in huge numbers, with the sales pitch that they made touching wood for luck (an internationally recognised apotropaic act) instantly possible on any occasion. The number of portable charms and their forms is intriguing; less enticing is the knowledge that the various Attleboro companies in Massachusetts USA, possibly the largest source of cheap trinkets in the world, were fabricating and shipping them to Europe at great benefit to themselves.

This is a tightly packed and absorbing read, difficult to summarise in a short review, but well worth pursuing as a synopsis of the western European mind-set as the world tottered into the 20th century and the modern, mechanised, world where age old fears were exposed once more to be salved, perhaps as they ever shall be, with a gimcrack selection of charms, faith and magic.

Review by: Rebecca Ireland

Book available from Amazon, hardcover : 304 page,

ISBN-13 : 978-0198794554 currently on offer at £10.68

paperback: ISBN-10 : 01987945 £12.99

kindle edition: £10.15

New and secondhand copies are periodically available on eBay.