GAMING UP THE WALLS

At the Making Your Mark Graffiti Symposium held at Southampton in September 2019, Raking Light’s Anthea Hawdon gave a talk on merels and other other boardgames. If you missed that, or would just like to re-visit the subject, read on….

Introduction

‘Merels’ is a strategy game of which there are several variants, a well- known version of which is Nine Mens’ Morris. These types of game were popular pastimes in the Middle Ages, although their origin is much older. Merels boards and similar versions are found as historic graffiti in both sacred and secular buildings, and found on both horizontal and vertical surfaces. This article will give an overall history of merels boards and explore the types and symbols of gaming boards that can be found in religious contests using case studies found with a sample of country churches of Essex. I’ll compare the spatial distribution of these boards with other known apotropaic marks inscribed as graffiti, and look at whether merel-type graffiti can be considered apotropaic in their own right or are merely prosaic. I’ll also apply deeper interpretation to aid understanding of the symbolism within merels boards and I hope that further debate will be stimulated and further recording prompted of these fascinating graffiti forms.

Gaming up the Walls

In 1699 William Garrett and Edward Christian were had up in front of the church court of Lezayre parish on the Isle of Man for the offence of “Makeing Nine-Holes with their knives upon Sunday after evening prayer.” [i] What Garrett and Christian were doing was playing a game. What they were making was a merel. And it is that division between the game and the symbol of the game board that lies at the heart of the research into these symbols. On the one hand we know exactly what these symbols are (we have rules for how to the play the games), on the other hand, their presence in places where they could not have been used as gameboards is something of a mystery.

Merels as Games

What are merels?

Strictly speaking, “merels” is another name for the game probably better known today as “Nine Mens’ Morris”. It also goes by the name of marells, marl, marriage, merryholes, merrypeg, miracles, morris and murrells, depending where you are in the country. In Germany, it is called, muhle. In France, it is marelles, or sometimes jeu du moulin.

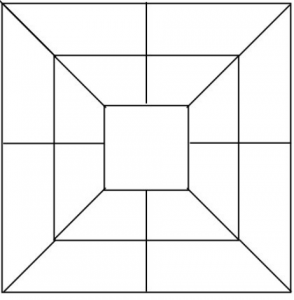

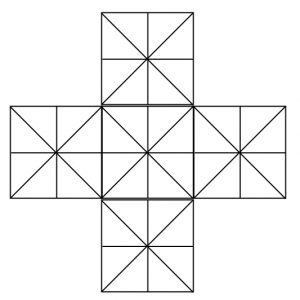

Harold Murray in his book, A History of Board Games Other Than Chess[ii] , puts it in the classification of Games of Alinement [sic] and Configuration as a Three in a Row Game. Today you will usually find Nine Men’s Morris boards in this configuration,

but this is also another common variant.

The nine in Nine Men’s Morris comes from each player having nine pieces. You play by placing, and then moving, pieces around the board so that you create rows of three. Once you have achieved this you can remove one of your opponent’s pieces and the game goes on until one player wins by reducing their opponent to only two pieces.

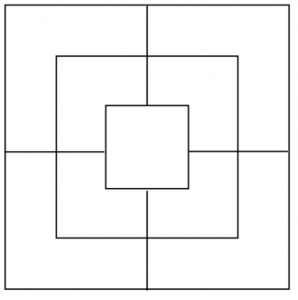

A simpler version of this is Three Men’s Morris, also called Lesser Merels or Nine Holes. Murray gives four possible boards for how this is played.

In this game, you have only three pieces each and the aim is to simply move them so that they form a row.

If this was a piece on games and gaming then that would be where this description would end, but here we’re concerned with graffiti and the category of ‘merels’ has expanded to include a couple of other games which are not part of the merels family.

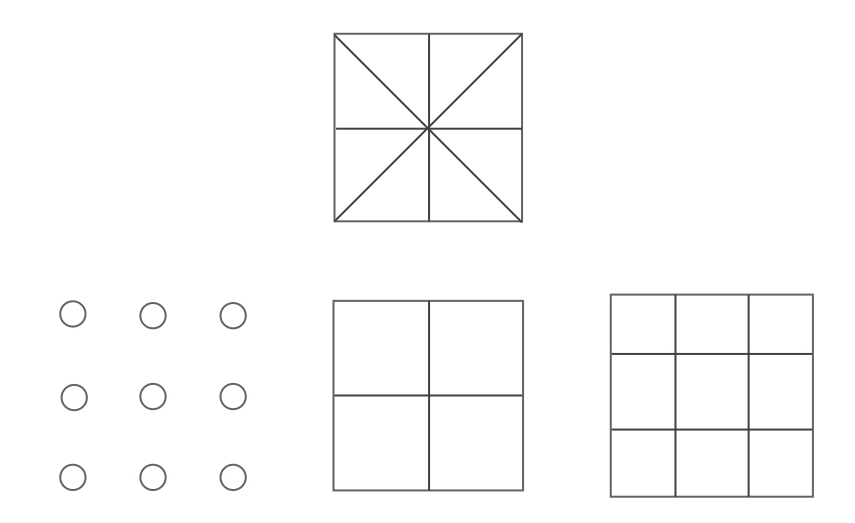

These include Alquerque and Fox and Geese.

Murray put Alquerque under the category of War Games and ‘games with the leap capture and moves along the marked lines of their boards’. It plays very much like draughts with the sacrifice and capture starting from the first move.

Fox and Geese is a Hunt Game, according to Murray. It is played one fox against 13 geese. The fox tries to take the geese by jumping over them into an empty point. The geese try to herd the fox into a position where it cannot make another move.

You can see from the board layouts for alquerque and fox and geese they share a lot of similarities with the merels games, especially with the Three Men’s Morris layout. Indeed Italy uses “marelle” as the name for alquerque .[iii]

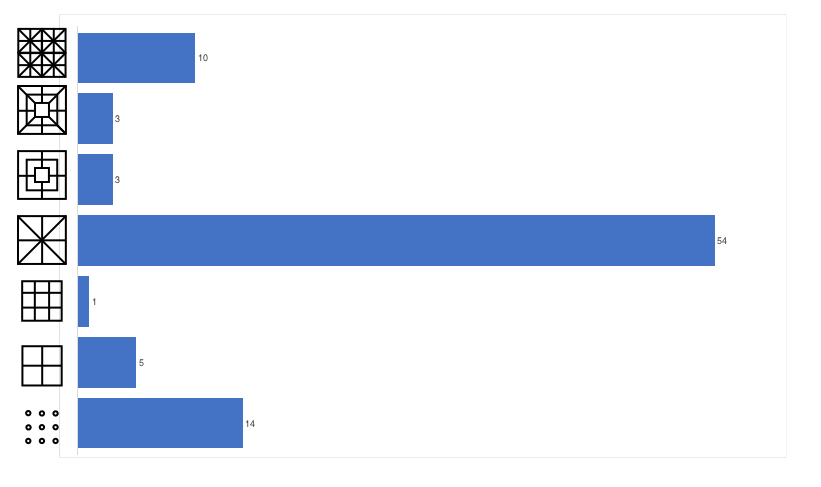

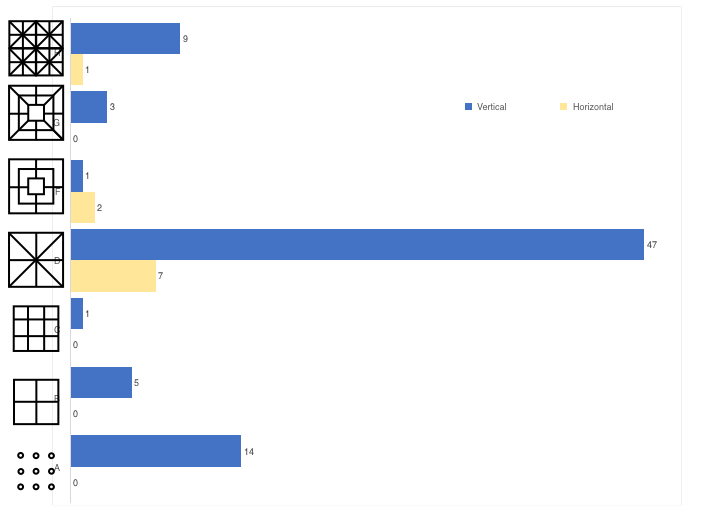

So much for the games. What about graffiti? Well, all of these game boards appear scratched on stone and wood in both horizontal and vertical positions, of playable and non-playable sizes. If we take Murray’s original typography and add in extra categories for alquerque and fox and geese, in my survey of 43 Essex churches, 28 churches had merels with the following distribution by type.

We can see that it is actually the Three Men’s Morris board layout that is the most common.

The earliest mention of a three-in-a-row game comes in Ovid’s Ars Amatoria. In Book 3, Part 8, he recommends women to learn to play games because ‘playing often brings on love’. His suggestions include one where:

‘A smaller board presents three stones each on either side,

Where the winner will have made his line up together.’[iv]

The clearest descriptions of Nine Men’s Morris, Three Men’s Morris and Alquerque occur in Alphonso X’s of Spain’s 13th century Book of Games[v]. Board layouts and rules are given for all three games including some variations with dice.

The archaeological record of the British Isles has many merels showing up in monastical sites in Dryburgh and Arbroath in Scotland[vi] and Whitby in England[vii]. There appears to be an ecclesiastical or monastical fondness for the game. They appear in many cathedral cloisters including Westminster Abbey, Salisbury and Gloucester[viii]. Parish churches also have playable merels boards where people could sit, such as this example from Great Sampford church in Essex.

Some recorders of these boards have assigned responsibility for them to schoolboys at monastic or cathedral schools[ix]. This does not appear to be solely the case as a manuscript from Cerne Abbas abbey[x] has examples of both chess puzzles and Nine Men’s Morris puzzles on consecutive pages. In addition, the Rule of the Knights Templar forbids a brother from playing “…no other game except Marelles, which each may play if he wishes for pleasure…”[xi]. This is born out by many merels boards carved into the fabric of both Templar and Hospitaller castles in the Holy Land[xii].

If the clergy had more leisure to play the game, it was not restricted to monastic sites. Gameboards have been found in such diverse secular sites as a Welsh hillfort[xiii] , a spoil heap near Creswell Crags in Derbyshire[xiv] and a fine alquerque board on a windowsill in Hampton Court Palace.

As that last example shows, the games continued to be popular through the early modern period to the 19th century.

The most famous mention must surely be that in a Midsummer Nights’ Dream where Shakespeare have Titania lament that “the Nine men’s Morris board is filled up with mud ”[xv]. This would be a board carved into the turf, such as that used by cow herders in Waugh’s Poly-Olbion[xvi] , a trip round the counties of England in rhyming couplets. Here it is Three Men’s Morris or nine holes, which his ‘wags’ neglect while they play the game on the heath.

Impromptu boards seem to be a common thing, such as with our church bothering duo from the start of this paper, scratching out a board with their knives. Other reporters of seeing the game played write about the games being marked on the side of a pair of bellows or chalked on the crown of a hat[xvii] and also on corn bins in stables[xviii]. This should make anyone who is now studying and researching merels take a cautious approach to assigning protective or ritual significance to merels found outside of obvious playing areas. It may be best assumed that any example of a horizontal, playable merels board was used for game play rather than ritual protection until proven otherwise.

If all merels graffiti hunters were finding were purely game boards then, I suggest, their study would still be a worthwhile occupation. However, there is clearly something else going on. Significant examples of merels, such as this one built into the wall of an old inn in the Loire valley in France, preclude being played on.

Nine Men’s Morris Symbolic Meaning

For Nine Men’s Morris there has been a good deal of research into its possible meaning.

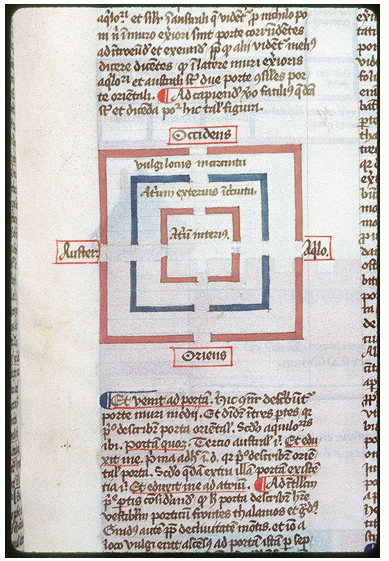

One of the most common takes on the Nine Mens’ Morris board is based around the concept of the ‘triple enclosure’[xix] . This is suggestive of temple buildings where you could have outer courtyard, inner courtyard and the temple sanctuary itself. The 1st or Solomon’s Temple in Jerusalem (Kings and Chronicles) and its replacement prophesied in Ezekiel Chapter 40 have such a structure. Indeed in the 15th century manuscript, Postilla in Bibliam[xx] the courts of the temple are described in a way very similar to the Nine Men’s Morris Board

This earthly Temple and the Heavenly Jerusalem in structure has been the focus of several works of hermeticism and occultism from the middle ages to the present day.

It is also worth pointing out that the people of the middle ages did not need to go very far to see the reality of such a structure in their own lives. A castle structure of outer wall or moat, inner wall and bailey rarely looked as neat as a game board, but the theory was the same.

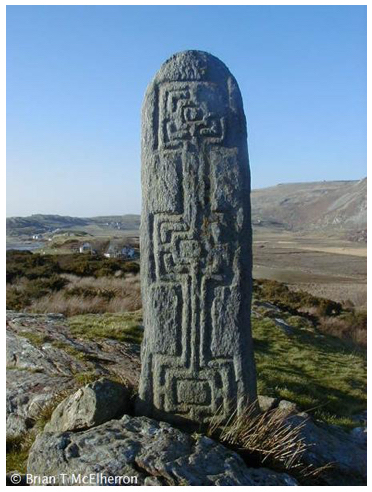

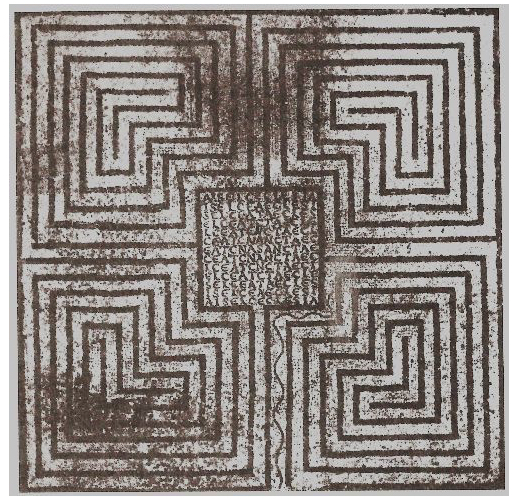

It is also conceivable that the board comes under the heading of square labyrinth such as displayed on the coins from Knossos

and also the cross at Glencolmcille, Country Donegal.

A mosaic floor from the Roman fort at Caeleon in Wales also demonstrates a concentric square layout[xxi], with the Church of Reparatus in Orleansville in Algeria[xxii] having four lines coming into a central square as does the Nine Men’s Morris board.

Nicolau, in his doctoral thesis[xxiii], describes the merels board as ‘an orientated cosmogram, with different sectors or barriers which have to be crossed to reach the center.’ Nigel Pennick likens the merels board to the ziggurats of Mesopotamia as representations of the cosmic mountain[xxiv] .

Three Men’s Morris Symbolic Meaning

Much less research has been carried out on the Three Men’s Morris board. This is a gap in the knowledge as the numbers from the churches in Essex show that it is by far the most common merel both vertically and horizontally.

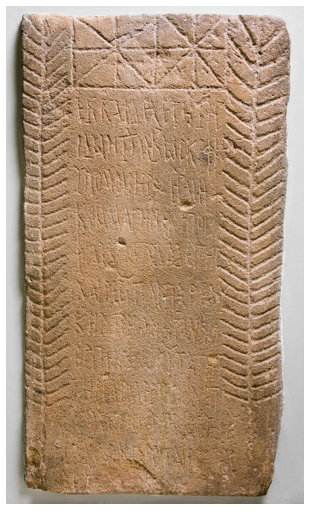

The shape of an eight-pointed square has some historic and possible symbolic status. The Brough Stone from near Stainmore in Cumbria is a gravestone for a boy called Hermes from Syria, who was at the Brough Roman fort and died in the 3rd century CE. Palm leaves and two squares which decorate the stone could be references to the god Hermes[xxv] .

In a Christian frame of reference, the eight armed cross has its own meanings. It known as the baptismal cross in the Catholic church. Eight being the days between Christ’s entry into Jerusalem and his resurrection. Baptismal fonts have eight sides for the same reason.

There is also an old Christian monogram where the Greek letter Chi, for CH, is superimposed on a Greek cross[xxv].

Also very similar is the ICHTHYS circle where the eight spoked wheel contains the letters for I, CH, TH, Y and S.

Adding to the mix is a magical sigil or character of eight spoked star with dots at the end of the spokes. It stands for God and heaven[xxviii]. Here is an example from the chancel arch at Finchingfield church. Note the merels underneath it.

The shape is also very similar to the healing charm recently publicised by the Wellcome Collection[xxix] . The charm consists of five crosses, but arranged in a way that is very reminiscent of a Three Men’s Morris board. There are several ways of arranging five crosses, but clearly this shape had some meaning for those who used it.

It is not necessary to play the game of Nine Holes to have lines between the holes. Mickelwhite lists examples found in the cloisters of Westminster Abbey, Norwich and Canterbury Cathedrals.

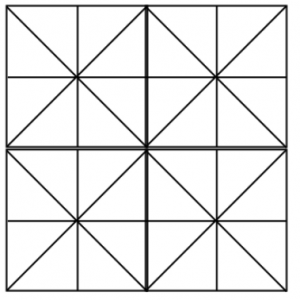

All these examples are horizontal and playable. But there are also two vertical examples in the Bradford Upon Avon Tithe Barn. This building is covered in compass and daisy wheel designs, clearly there to protect the produce brought in for its associated monastery. Among that mass of protective marks are two designs like this example.

It could be that this was a piece of reused stone, originally marked out by the builders for a game board. But we’ve heard these arguments before with all graffiti.

The nine holes symbol shows up occasionally in that collection of marks, usually called ‘dot patterns’. Three by three is the Trinity three times over. Nine also has its own symbolism and is the base for the novena prayers which are carried out for nine days.

By no means all dot patterns are nine holes game boards, but it would help merels research tremendously if occurrences of Murray’s type 1 board could be noted as possible merels rather than only dot patterns.

I wish I had a neat conclusion to give you at the end of this article. The games that make up the merel graffiti family stretch back to the middle ages in Europe and, in some cases, considerably beyond. It also appears that they have been used as a symbol almost as long. Their study requires a balancing act between the mundane, prosaic game boards and the symbolic, possible protective symbol.

Perhaps it might be best to leave the last words to be those of the 14th century mystic Meister Eckhart: ‘This play was played eternally before all natures… The Son has eternally been playing before the Father as the Father before the Son… Sport and players are the same.[xxx] ‘

Notes

[i] Journal of the Isle of Man Museum, VolIII, No 53, 1953, p245

[ii] Murray, HJR. A History of Board Games Other than Chess. Clarendon Press, 1952

[iii] Murray, HJR. A History of Board Games Other than Chess. Clarendon Press, 1952

[iv] Moore, Bertram Percy. The Art of Love : Ovid’s Ars Amatoria. Blackie, 1935

[v] Alfonso X. Libro de los Juegos. 1283.

[vi] Robertson, Norman. The Game of Merelles in Scotland. Proceedings of the Society of Antiquaries of Scotland, Vol98, 1966

[vii] Hall, Mark A. “The Whitby Merels Board.” Yorkshire Archaeological Journal, Vol 77, 2005, p25

[viii] Micklethwaite, J. T. “On the Indoor Games of School Boys in the Middle Ages.” Ar-chaeological Journal, vol. 49, no. 1, 1892, pp. 319–328.

[ix] Micklethwaite, J. T. “On the Indoor Games of School Boys in the Middle Ages.” Ar-chaeological Journal, vol. 49, no. 1, 1892, pp. 319–328.

[x] Hunt, Tony. “‘DELICIAE CLERICORUM’: INTELLECTUAL AND SCIENTIFIC PURSUITS IN TWO DORSET MONASTERIES.” Medium Ævum, vol. 56, no. 2, 1987, pp. 159–182.

[xi] Upton-Ward, JM (trans); The Rule of the Templars; Boydell Press; 1992

[xii] Boas, Adrian J. Archaeology of the Military Orders : a Survey of the Urban Centres, Rural Settlement and Castles of the Military Orders in the Latin East (c. 1120-1291). Routledge, 2006

[xiii] Crew, Peter. “A SMALL, MERELS BOARD FROM BRYN Y CASTELL.” Journal of the Merioneth Historical and Record Society (1981)

[xiv] HALL, MA, and PB PETTITT. “A PAIR OF MERELS BOARDS ON A STONE BLOCK FROM CHURCH HOLE CAVE, CRESWELL CRAGS, NOTTINGHAMSHIRE, ENGLAND.” Transactions of the Thoroton Society of Nottinghamshire 111 (2008): 135.

[xv] Shakespeare, William. A Midsummer Night’s Dream. Act 2, Scene 2.

[xvi] Drayton, Michael. Poly-Olbion by Michaell· Drayton Esqr Poly-Olbion. Printed by Humphrey Lownes for M Lownes. I Browne. I Helme. I Busbie.

[xvii] Hone, et al. The Every-Day Book; or, The Guide to the Year: Relating to the Popular Amusements, Sports, Ceremonies, Manners, Customs and Events, Incident to the 365 Days in Past and Present Times … Printed for William Hone, and Sold by All Booksellers in Town and Country, 1825.

[xviii] Wise, John R. Shakspere : His Birthplace and Its Neighbourhood. Smith, Elder and Co., 1861.

[xix] Guénon, René Symboles Fondamentaux De La Science Sacrée. Gallimard, 1962.

[xx] Nicolaus de Lyra. Postillian In Bibliam. Tours-BM-Ms 0054, f.240

[xxi] Smith, D. J. “The labyrinth mosaic at Caerleon’.” Bull. Board Celtic Stud 18 (1959): 304-10o

[xxii] Matthews, William Henry. Mazes and labyrinths: their history and development. Courier Corporation, 1970.

[xxiii] Pujol Nicolau, Gaspar. Traditional Cosmological Symbolism in Ancient Board Games. Diss. Universitat Internacional de Catalunya, 2009.

[xxiv] Pennick, Nigel. Games of the Gods: The origin of board games in magic and divination. Rider, 1988.

[xxv] Scarth, Prebendary. “On a Funereal Stone Inscribed With Greek Hexameters, Discovered at Brough-Under-Stanemore, Westmoreland in Restoring the Church, AD 1879.” Journal of the British Archaeological Association: First Series 42.3 (1886): 294-299.

[xxvi] Lehner, Ernst. Symbols, signs and signets. Courier Corporation, 2012.

[xxvii] Valliant, James S., and C. W. Fahy. Creating Christ: How Roman Emperors Invented Christianity. Crossroad Press, 2016.

[xxviii] Jackson, MB. Sigils, Ciphers and Scripts. History and Graphic Function of Magick Symbols. Green Magic, 2013

[xxix] Collection of medical receipts in English and Latin (Leech-Books, IV)

[xxx] God and Games: Toward a Theology of Play by David L Miller, 1970, Harper Colophon.